Imperial China, 2018

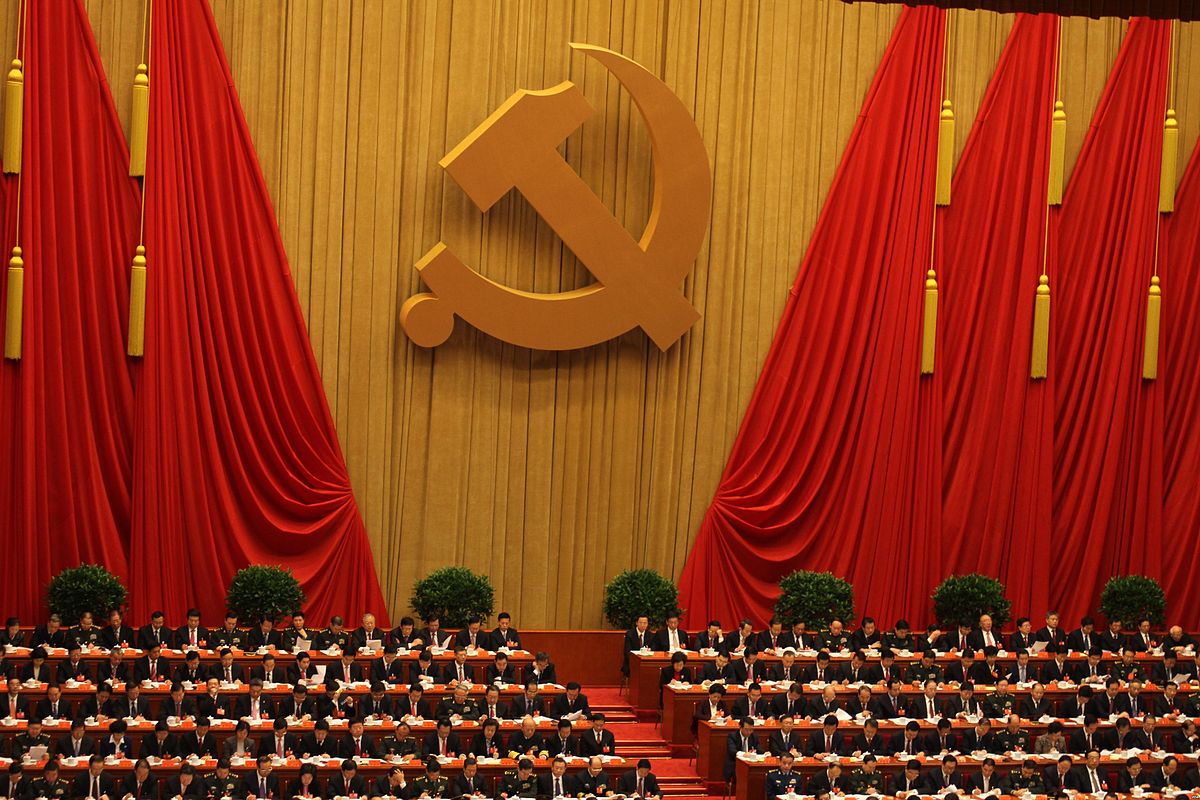

Russia is not the greatest security threat to the West and the United States. Neither is ISIS nor the other muslim jihadist movements. A newly imperial China holds that distinction.

China’s Ambitions

China’s distinctive menace to the rest of the world arises from being a lot more ambitious than Russia. All Russia wants right now is to claw back its empire in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states. This is the empire lost with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The muslim jihadist movements, wanting to control the entire world, are just as ambitious. However, they lack the ability to project power possessed by China. Communist China however is fast becoming an imperial China.

Like the jihadist movements, Communist China wants to control and feed upon the entire world. This ambition is revealed to us in five different projects, which complement each other.

- The “Made in China 2025” project.

- China’s “Belt and Road” Initiative.

- China’s project to claim and dominate the East and South China Seas.

- China’s rapid military and naval buildups.

- China’s efforts to steal technology from the rest of the world, particularly the United States.

Because these projects mutually reinforce each other, they are not completely distinct and independent as the list suggests. Rather they are merely different modes or processes China is following to dominate the rest of the world.

Chinese Competition with the West

Just how non-hostile to the West is the Chinese search for global power? Another way of stating the question is to ask: Is China a “revisionist state” or a “status quo state?” In the parlance of foreign affairs, a revisionist state is one seeking to change the current international system; a status quo state is content to support the existing international system.

Just because China is seeking to become a regional hegemon, indeed to supplant the U.S. in that role in East and South Asia, does not mean it will become a hostile adversary. It does not mean China will be a threat to core U.S. interests. Just because China is working hard to supplant the U.S. as Asia’s dominant naval and military power does not necessarily presage a war between the U.S. and China. This is the view of a number of diplomats and academics.

However, a great many of our Asian and European allies would beg to differ from that benign view. Charles Edel, a senior fellow at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, wrote recently on the American Interest website,

Given Trump’s erraticism and transactional approach to foreign policy, it is important not to mistake the general trend of a hardening trade relationship with China across the West. A desire to put more pressure on China is not simply a Trump phenomenon. Indeed, it’s one of the few areas where there’s bipartisan agreement in the United States and among its traditional allies Japan, Canada, and Europe right now.

Furthermore, Edel questions Chinese sincerity in claiming benign motives when he notes.

First, there is emerging consensus that under his drive to solidify the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on the country, Xi Jinping has accelerated China’s embrace of authoritarianism in a way that fundamentally undercuts Beijing’s reformist rhetoric. The result is a country that is increasingly closing itself—and its markets—to outside trade and investment, insisting that the price of doing business in China is forced technology transfer, and lurching away from transparency

Why, Edel asks, would China seek to “dominate the core components of a future [world] economy by investing in cutting-edge innovation in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, robotics, and aerospace industries among others, while also increasing Chinese acquisitions of U.S. and Western firms?” Why would China over-invest in industrial goods like steel beyond any possibility of recovering a profit, only to dump those products in the West at prices below production costs? Could the Chinese be attempting to make the West dependent on China for those products? How could such a dependence be exploited in the future? If the West could be made dependent enough, China could dictate the solutions to future problems with the West. Paraphrasing Shakespeare’s Hamlet, something is rotten in the state of China.

Those with a more charitable view of Chinese intentions cite China’s Belt and Road initiative as a stimulus for international trade for developing countries, a kind of Chinese Marshall Plan. This belt in their view is meant to transmit Chinese “soft power” from the East toward Europe. Yet, if the fears in the previous paragraph are correct, that belt could also transmit Chinese economic dominance and a much harder kind of power.

Non-Chinese peoples who might come under the control of China should look at the fate of muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang, China. Ellen Bork, also writing for the American Interest, tells us,

Reports from rights groups, academics, and reporters show a staggering increase in the scale and intensity of repression of Uighurs in China’s far northwest region of Xinjiang. . . .

PRC [People’s Republic of China] repression of the Uighurs has a long history. After the region came under PRC control in 1949, the Party used it to house prison camps and nuclear testing facilities and exploited its natural resources. The authorities targeted language, religion, and education, and those who objected risked being labeled as “separatists.”

The new policies of mass incarceration in detention and re-education camps mark a qualitative and quantitative worsening. They bear the hallmarks of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s rule: the revival of Marxism-Leninism, the campaign to “Sinicize” religion, and the desire to secure Xinjiang, the jumping-off point for the land component of Xi’s legacy mega-project, the “Belt and Road Initiative.” . . . Adrian Zenz estimates, conservatively, “a detention rate of up to 11.5 percent of the region’s adult Uighur and Kazakh population.”

There are other Chinese acts strongly suggesting their view of the non-Chinese world is not particularly benevolent. For example, China is rapidly converting the South China Sea into a militarized zone, with artificial islands acting as unsinkable aircraft carriers. The map below shows not only Chinese claims in the South China Sea, bounded by the red curve, but the claims of other countries denoted by curves of other colors as well. Viewing these overlapping curves, you can appreciate the potential for conflict.

Wikimedia Commons / Voice of America

The importance of China’s South China Sea claims for the West is explained by the following fact. According to Robert D. Kaplan, chief geopolitical analyst for Stratfor and a former member of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board, more than half the merchant ship tonnage every year passes through the South China Sea. The oil transported through this choke-point enroute to East Asia is three times what passes through the Suez Canal and fifteen times what goes through the Panama Canal. Since Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines all have competing claims, the chances for armed conflict over these islands are very significant. To grant China control of the South China Sea would create a significant threat to Western trade with Asian nations.

Almost equally concerning are China’s claims in the East China Sea, illustrated in the map below.

What China has done is to declare the marked area an “air-defense identification zone.” China’s defense ministry says any aircraft entering the zone must obey any commands given them, or face “emergency defensive measures.” Japan claims the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands within the zone, as does Taiwan.

Observing China’s imperialistic predilections, many of China’s neighbors are getting very nervous themselves, leading to unexpected alliances to deter China’s appetites. In particular, Japan and South Korea, two countries with historically strained relations arising from World War II, are discussing military cooperation.

More about these tensions with China’s nearest neighbors can be found in the post A Nervous Face-of Against Chinese Imperialism.

All of these considerations strongly suggest China is not a benevolent, peace-seeking growing power simply trying to fit in with the world system. Instead, it appears much more to be a revisionist power, seeking dominance over as much of the rest of the world as it can acquire. If this is the case, there is a lot more riding on Donald Trump’s trade war with China than fairer trade.

Views: 1,823