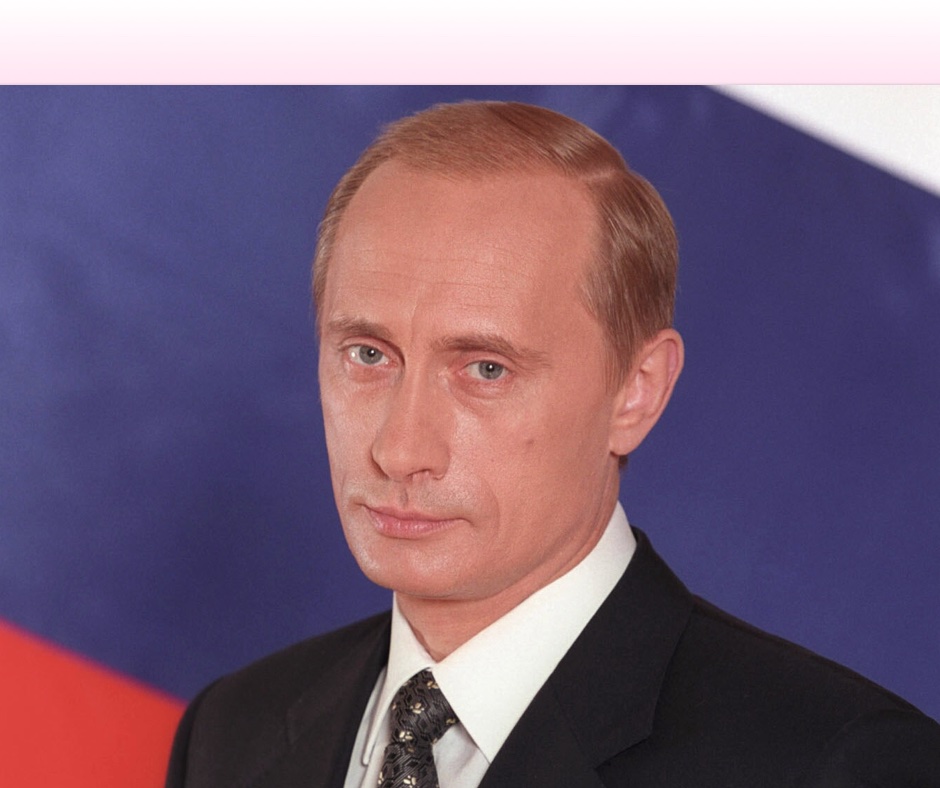

Putin’s Purges

Der Russische Führer, Vladimir Putin

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Kremlin.ru

ANDERS ÅSLUND has become an indispensable analyst of that “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”, as Sir Winston Churchill once described Russia. As I intend to cite Åslund’s thinking on Russia a great deal, I will relate some of his curriculum vitae to convince you he is indeed a person to whom you should pay attention.

Between 1989 and 1994 Åslund was Professor of International Economics at the Stockholm School of Economics. In 1989 he became the first director of the Stockholm Institute of East European Economics, which later became the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As this institute was founded while the Soviet Union still dominated Eastern Europe under the Warsaw Pact, Åslund was inevitably interested in Russia.

Wikimedia Commons/Voice of America

In 1990 Åslund wrote a controversial opinion-piece in the prestigious Swedish daily, Dagens Nyheter, that drew parallels between the social democratic policies of Sweden and the collapsing communist regimes of the Warsaw Pact. This anti-socialist article inspired a flood of answering articles from the ruling Social Democratic party. Åslund’s opinion so stung the ruling party that the Prime Minister Ingvar Carlson honored him by attacking his ideas in the Swedish Parliament.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Åslund worked with Jeffrey Sachs and David Lipton, giving economic advice to the Russian reform government under President Boris Yeltsin and Acting Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. He summarized his views in a book with the excessively optimistic title How Russia Became a Market Economy. Later he gave economic advice to both President Leonid Kuchma of Ukraine and President Askar Akaev of Kyrgyzstan. Both by his experience and expertise, he demands our attention.

The Crony-Capitalism of Fascist Russia

Two posts back, in Russia: A Classic Fascist Power I gave you the reasons for considering Russia’s government, and economic and social organization, as classically fascist. What gives Russia its characteristic fascist character is partially its economy’s current organization as crony-capitalist. The stillborn Russian free-market economy under Boris Yeltsin was killed by corrupt sales of state assets, in the guise of privatization, to well-connected former Communist Party members. They were the only domestic economic agents —surprise! surprise! — to have enough capital to buy the newly privatized state companies. The Russian government had a choice either to sell to foreign investors or to sell to the former-communist Russian oligarchs. Yeltsin chose the latter.

In the nomenclature of David Kang, there are three major types of crony-capitalism:

- Rent seeking and state capture by Big Business controlling a weak, disjointed state government.

- A balance of power between government and Big Business, which balance out each other’s influence in politics and economics. In this form of crony capitalism, the state and Big Business hold each other as mutual hostages.

- Business is disunited and dominated, and powerful state organizations completely capture control of the disunited private companies. This is sometimes called “the predatory state”.

Eventually, under any of these three scenarios, the system will collapse into a fascist state; the three different scenarios merely influence who is on top after the fascist collapse. In the Russia of Boris Yeltsin, the crony-capitalism was predominantly of the “mutual hostage” type, although an argument could be made for the “predatory state” type.

After Yeltsin was succeeded by Vladimir Putin, the power of the former communist oligarchs who had captured the “privatized” companies waned, as Putin increasingly consolidated his control over the various oligarchs. After Putin took control, Russia was without any doubt a “predatory state”. As in any crony-capitalist state — or for that matter in a socialist state of any nature — economic performance has suffered with the lack of free-market controls over capital allocation. The socialist “economic calculation problem” remains — and probably always shall be —unsolved.

Putin’s Recent Purges

True to the heritage of Adolf Hitler and of Stalin, Vladimir Putin has been purging some of his old associates recently to strengthen his hold on power. Anders Åslund has written in the post Putin’s Great Purge on The American Interest website that Putin has been “dismissing one senior KGB associate after another.” These members of the KGB are also typically crony-capitalist oligarchs.

Åslund notes:

In recent years, Putin’s power has been based on three concentric circles. At the center, a group of his contemporary KGB generals sit in the Kremlin and at the top of the security agencies. A second group of his contemporaries from St. Petersburg and the KGB is in charge of the big state corporations. A third group of cronies from St. Petersburg make fortunes in the private sector from privileged state procurements. These Putin protégés were seen as nearly untouchable, with only the odd, accidental departure.

Unlike Hitler’s and Stalin’s purges, Putin’s pruning of the tree of power has generally been non-lethal. Those purged have generally retired, been fired, or at worst have been sent to prison. The first to be forced out was Vladimir Yakunin in August 2015, who retired as the CEO of the Russian Railways. Only ten days later, the head of the state hydropower company was fired, and later sent to ten years in prison for corruption. Then last February, Vladimir Dmitriev, the CEO of the big state bank, Vnesheconombank, was lucky enough to be only required to retire. Åslund informs us that “Yakunin and Dmitriev were widely considered KGB generals.” Perhaps, you might ask, was Putin really only getting rid of the rotten wood? After all, is not crony-capitalism almost synonymous with corruption? Yet, Åslund disabuses us of this idea when he writes:

In each case, there were allegations about gross mismanagement and corruption, but that was hardly the cause of their ouster, because Putin is showering ever more state money on other, rather more corrupt cronies, including the major state contractors Arkady Rotenberg, Gennady Timchenko, Yuri Kovalchuk, and Nikolay Shamalov. Russia’s ruling elite is so pervasively corrupt that larceny cannot be a reason for dismissal, while it is a standard excuse.

In the process Putin has rebalanced power between several state security agencies, one of which — the National Guard with 170,000 troops — is newly created. From what Åslund tells us, Putin is dividing the security services into two groups, which he is balancing one against the other. On one side are the two organizations into which the KGB split after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Federal Security Service and the Foreign Intelligence Service. On the other side are a small elitist presidential guard and the new National Guard. As Åslund puts it, “Putin has supported the security services and encouraged their rivalries, as Mark Galeotti has analyzed …” Åslund goes on to list a number of other purges, but pursuing them is probably getting too much into the weeds. In summary, Åslund writes:

In July, Putin appointed several regional representatives and governors. Two new governors are his former bodyguards from the FSO (the small presidential guard), while most of the new appointees were drawn from the FSB (the Federal Security Service, the main successor agency to the KGB). The security services are on the rise, but Putin’s old friends are on the decline.

What does it all mean? Åslund cites a Russian journalist in Ukrainian exile, Yevgeny Kislev, who sees a parallel with Stalin’s great purge in 1937. In that purge Stalin got rid of all who had known him when he was young as well as all the old Bolsheviks who could look down on him. In the same way, Kiselev suggests, Putin is getting rid of all who knew him as a young, generally unsuccessful KGB spy and a mediocre officer in St. Petersburg. That would be the reason for the sacking of so many KGB generals. It would also explain Putin’s promotion of young junior officers “who owe everything to him and will obey unquestioningly.” Finally, “…needless to say, this purge has nothing to do with reforms. On the contrary, it is all about concentrating power in Putin’s hands so that he can continue to rule without reforms.”

I would like to note that this description of Putin’s purges is straight out of chapter 10 of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom [E2], entitled Why the Worst Get on Top. There Hayak writes,

There are strong reasons for believing that what to us appear the worst features of the existing totalitarian systems are not accidental by-products but phenomena which totalitarianism is certain sooner or later to produce. Just as the democratic statesman who sets out to plan economic life will soon be confronted with the alternative of either assuming dictatorial powers or abandoning his plans, so the totalitarian dictator would soon have to choose between disregard of ordinary morals and failure. It is for this reason that the unscrupulous and uninhibited are likely to be more successful in a society tending toward totalitarianism. Who does not see this has not yet grasped the full width of the gulf which separates totalitarianism from a liberal regime, the utter difference between the whole moral atmosphere under collectivism and the essentially individualist Western civilization.

In a footnote to the chapter, it was noted how this reality implies the occasional purges one might find in a totalitarian society. Purges such as the Night of the Long Knives in Nazi Germany. Hayek had seen it all before.

Why We Should Be Interested

This is all very interesting, but why is it important for us? For one thing such totalitarian behavior helps to limit the power of the Russian regime. Any society that directs its attention and resources to an occasional war with itself absorbs time and resources from any conflict outside their country. It also eliminates the possibly competent and useful contributions to the nation from those who are purged, as well as alienating some of the friends of those purged.

Also, the same habits of thought that give a ruler the need to absolutely control the thoughts and actions of those who follow him give rise to a need to absolutely control the direction of his country’s economy. By purging those officials who are managing the economy because of their disagreeable opinions, the autocrat injects further disruptions into the economy’s internal workings. These are disruptions over and above the ordinary disturbances of socialist control on microeconomic supply-demand relationships. I gave a very short discussion of how these problems could undermine the military power of each of the members of the Russia-China-Iran Axis in the post Achilles Heel of Autocrats: Their Economy. I gave this idea some further thought in Russia Becoming Cautious?

One final thought on Putin’s purges is introduced by Anders Åslund in his post Why We Need Kremlinology Again. There are several definitions of “Kremlinology” in circulation, as Åslund notes in his introductory paragraphs, but the one he finds most apropos is the following: “The art of observing, deducing, and guessing what is really happening within a secretive organization.” With Putin seeking to recover the lost Russian imperium’s states of Eastern Europe and the Baltic (see Putin’s Russia and the West and Consequences of a Weak US President), we have a great need to discover the Russian state’s intentions and plans, as well as what conflicts might exist between Russia’s political, economic, and military leaders. Observing their capabilities is a much easier problem. Since purges make intentions and plans more volatile, the new need for kremlinology is all the more acute. The problems we have with Russia today are almost identical to those of the old Cold War.

Views: 3,315