Trump Becomes More Convincing About Foreign Trade

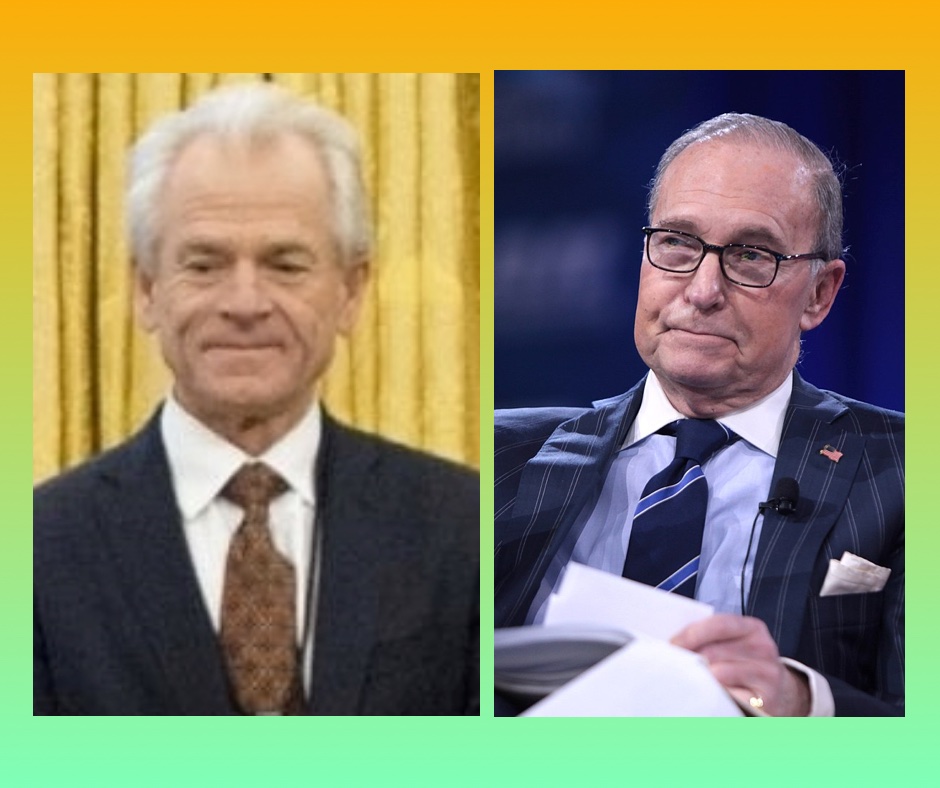

Peter Navarro and Larry Kudlow, Donald Trump’s top advisors on foreign trade.

Left: Prof. Peter Navarro Wikimedia Commons / White House

Right: Larry Kudlow Wikimedia Commons / Gage Skidmore

I have surprised myself. Until recently, my biggest disagreements with Donald Trump have been over the divisive issues of foreign trade. I have written several times expressing my differences. Consider my posts The Divisive Issue of Foreign Trade and Donald Trump’s Stupidity About Foreign Trade as evidence. Yet, as I consider Trump’s arguments, I have been startled by a dismaying discovery. Trump might actually have some very valid points!

The Difference Between the Law of Comparative Advantage and other Neoclassical Economic Laws

The roots of this reconsideration lie in a fundamental difference between David Ricardo’s law of comparative advantage and the other three major neoclassical laws of economics: the law of supply and demand, Say’s law of markets, and the law of marginal utility. The law of comparative advantage is the major justification for free-trade between nations.

The law of comparative advantage says if a country sells on the international market what it produces most efficiently, and buys what another country can produce more efficiently, both countries will maximize their wealth production. A more accurate, mathematical definition of a country’s comparative advantage over another country for a particular good can be found in the post How Probable is a Trade War With China. The point is, if country B has a comparative advantage over country A in producing a good, both sides will profit if B sells to A. This is true even if A can produce the good with less cost than B! The reason why is that A can then use the capital it would otherwise have used to produce the good for producing something else that it does far better. A qualitative explanation for all this can be found in the video below.

In fact, Ricardo’s comparative advantage is a way of applying Adam Smith’s idea of the division of labor to find a division of labor between nations. Just as a division of labor within a nation maximizes productivity and wealth production, so a division of labor dictated by comparative advantages will maximize wealth production among the nations.

Nevertheless, the efficient operation of the law of comparative advantage presupposes several things. Here we come up against the very fundamental difference between comparative advantage and the other three neoclassical laws. The other three laws are just as valid in any kind of economy, no matter how socialist or how free-market. Of course, they express themselves differently in different kinds of economies, but they are just as valid in any economy. Not so for comparative advantage.

In fact, the law of comparative advantage points to how countries can maximize their wealth production if those countries use comparative advantage to choose what to produce and sell on the international markets. Unfortunately, nothing forces countries to use comparative advantages to make such decisions. As we have learned to our cost with China, countries will often use other criteria to make their trade decisions. In the case of China, it is geopolitical power and domestic social peace for which they lust more than economic prosperity.

Yet, it is not just the decisions of other countries that determine the applicability of the law of comparative advantage. The decisions of our own country are just as important. If our country imports goods from other countries, we must find another use for the capital we formerly used to produce the imported good. We must use that capital to produce something else for which we have our own comparative advantage. If the domestic economic policies of government greatly discourage economic investment, no such redirection of capital will take place. This is a large part of the explanation for how economically barren the Obama era was.

What Donald Trump is telling us is that if other countries set tariffs and make other foreign trade policies independent of comparative advantages, then simply engaging in free-trade ourselves is ultimately destructive to our economy. How is this so?

The Problems With Free-Trade

Judging from Trump’s past statements during the 2016 campaign, he is not only inarticulate, but also lacking a great deal of knowledge about theoretical economics. Nevertheless, his two major advisors on foreign trade, Peter Navarro and Larry Kudlow, might explain the problems of foreign trade in the following ways.

First, when any country levies a tariff on an imported good, it increases the good’s cost to its citizens. To that country’s buyers of the imported good, the added cost looks no different than the production and other costs of the exporter. Therefore, even if the exporting country has an intrinsic comparative advantage in producing the good, a high enough import tariff will make it look like the exporter has no comparative advantage. The law of comparative advantage is subverted, and the desirable international division of labor is aborted. As a result, the productive capacity of both nations will not increase as much as it could have.

Second, the United States has historically been convinced of the economic desirability of free-trade. As a result the U.S. has entered into a number of trade agreements with other countries through the World Trade Organization (WTO), and before it through its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). As a result, the U.S. has generally accepted far higher import duties on its exports than other countries have on theirs. One result of declining U.S. tariffs in the face of higher import tariffs by other nations on U.S. products is that the U.S. imports more than it exports. The evidence is in the graph below.

Wikimedia Commons / James4

These observations explain why Trump is so fixated on other countries’ import tariffs on U.S. exports. In fact, a leading German business newspaper, the Handelsblatt Global, says Trump might have a point about EU tariffs. In a March 2018 article, they reported a leading German think tank, the Ifo Center for International Economics, came to this conclusion. The Handelsblatt Global reported,

“The EU is by no means the paradise for free traders that it likes to think,” said Gabriel Felbermayr, director of the ifo Center for International Economics, a division of the Munich-based ifo Institute. The European Union actually comes off as the bigger offender when compared to the US, he added. The unweighted average EU customs duty is 5.2 percent, versus the US rate of 3.5 percent, according to ifo’s database.

So when Mr. Trump complains of “massive tariffs” he is not that far off the mark in several cases. And he does complain. “If the EU wants to further increase their already massive tariffs and barriers on US companies doing business there, we will simply apply a tax on their cars, which freely pour into the US,” the president tweeted earlier this month. “They make it impossible for our cars (and more) to sell there. Big trade imbalance!”

Cars are a particular sore point. Imports into the US are not quite free, but pay a tariff of only 2.5 percent, compared with the EU tariff of 10 percent on US car imports. Some other examples from the EU include a 17 percent tax on apples and 20 percent on grapes.

Overall, tariffs totaling $5.7 billion were levied on US exports to the EU in 2015. The far greater volume of EU exports into the US were subject to customs duties of just $7.1 billion. This does not even take into account the inhibitory effect of the higher EU tariffs on the volume of US exports.

The opponents of Trump’s trade policies sometimes point out that no one is free from sin, not even the United States. For example the U.S. charges a confiscatory 350% tariff on some tobacco imports. Then again, one can justify that particular tariff, not with economic reasons, but on public health considerations.

Yet, tariffs are only the tip of the iceberg with our foreign trade problems. Non-tariff barriers also create obstacles to free-trade. In another March 2018 article, the Wall Street Journal editorial board reported on a doozy of a barrier to U.S. tech firms being thought up by EU technocrats. It has not yet been brought into existence, but it serves as an example for the kinds of things governments do. According to the Wall Street Journal,

The European Commission, the EU’s bureaucratic wing, is plugging for a 3% tax on revenues—no matter the profits—that large tech firms earn from sales in Europe. . . . For “large tech firms” you should read “American companies” since the rules are tailored to apply to the likes of Amazon, Apple, Google and Facebook . The tax proposal ensnares companies that sell digital advertising or provide a platform for online trade between third parties. This exempts such firms as brick-and-mortar department stores that sell designer handbags over their websites, no matter how digital the transactions look.

The measure would apply only to companies with at least €750 million in annual world-wide revenue and €50 million in sales within the EU. Europe wishes it had a tech company of that global heft.

In short, such an EU action would create a tariff that technically is not a tariff, one specifically designed for large American tech companies.

These kinds of examples and others arising from intellectual property theft and other forms of non-tariff barriers can be be multiplied many times. In the face of these examples, U.S. trade deficits with all of its major trade partners can only point to one thing: Comparative advantage is not a primary consideration in our partners’ trade policies. As Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross pointed out to a Davos panel last January, concessions made to the European nations in the aftermath of World War II are no longer appropriate. Trump is using the threat of tariff increases as a big two-by-four to get our trade partners’ attention, to tell them the trading system must change.

Views: 2,405