The Long-Term Economic Stagnation the World Faces

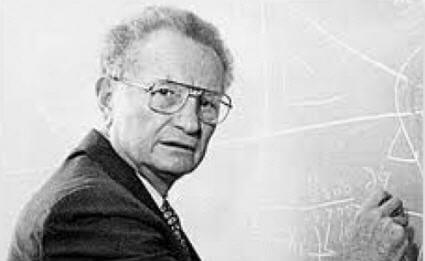

Alvin Hansen (1887-1975): Keynesian economist

who invented the Keynesian idea of secular stagnation

Photo Credit: Rugusavay.com

Larry Summer’s project to revive Alvin Hansen’s idea of secular stagnation is gaining in public visibility. Recently, a post on the Time magazine website, entitled This Theory Explains Why the U.S. Economy Might Never Get Better, discussed the idea sympathetically from the Keynesian point of view. As a different view you might consider the George F. Will post, Why the future will disappoint on the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review website.

When the depression era Keynesian Alvin Hansen first developed the idea he called secular stagnation, Keynesians were desperately looking for an explanation for why Keynesian ideas were not stimulating the economy as much as they expected. Hansen’s explanation was that all the factors generating growth, particularly technological advances and population growth, had been exhausted as sources of growth. As is typical of Keynesians, Hansen looked for a solution from the federal government in the form of constant, large-scale government spending. As soon as U.S. economic growth revived after the end of World War II, Keynesian secular stagnation and its Keynesian antidote were forgotten by all except academics.

Real Secular Stagnation

Today, however, Keynesians are facing the same dilemma that Hansen did. Whether it is monetary policy or government fiscal policy, all over the world the policies Keynesians have been advocating have simply not been working to produce healthy economic growth. Here in the United States we do not seem to be able to do much better on average than a little more than 2% per year. In fact that has very much been the rule for almost a decade. We see something very similar in Europe, as I mentioned in the post Europe’s Challenge: Evolve or Die. Since the end of the Great Recession in Europe, the Eurozone economy has not been able to achieve a GDP quarterly annualized growth rate of better than 1.6%, which is considerably worse than even our 2.1% average GDP growth rates. We can also see stagnating economies in China and Japan.

The economic stagnation we are seeing is then not only real but it is world-wide. It is also secular in the sense it is long-term. Particularly in the United States, Europe, and Japan, this stagnation has lasted at least a decade. For Japan one could argue the Japanese economic stagnation has lasted for almost three decades! There can be no argument against the proposition most of the world’s economies are undergoing a very real secular stagnation.

But are the Keynesian explanations for its cause and prescriptions for its cure correct? I think it is highly suggestive that both historical periods when Keynesians tried to use secular stagnation as an explanation, the Great Depression and the Great Recession, were periods during which economies evolved under dominant Keynesian policies.

The Current Keynesian Revival of Secular Stagnation

In the Time magazine post, written by Jacob Davidson, Davidson first reviews the historical data showing that there is in fact a very real secular stagnation. He then relates the rise of the original secular stagnation theory by Hanson, writing that

Grappling with the sluggish recovery that followed the Great Depression, Hansen predicted that slower population growth and a lower speed of technological progress would combine to thwart full employment, wage increases, and general economic expansion. In both cases, Hansen’s reasoning was the same: without new people entering the work force and new inventions coming onto the market, there would be less investment in new goods, employees and services. Without investment, fewer businesses would open or expand, growth would slow, and more workers would be unable to find jobs.

Davidson then notes:

Hansen painted an eerily familiar picture: “This is the essence of secular stagnation,” he explained, “sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions which feed on themselves and leave a hard and seemingly immovable core of unemployment.” He could have been describing 1938 or 2016.

Ever since Larry Summers got the ball rolling in the modern revival of Hansen’s secular stagnation, many economists have had a great many opinions on what has caused the current secular stagnation. Davidson quotes Berkeley professor Barry Eichengreen (who is a co-author with Larry Summers and many other Keynesian economists of an eBook on secular stagnation you can download here) to the effect that so many explanations of the causes of secular stagnation have been generated it is something of “an economist’s Rorchach Test.” One factor on which almost all contributors to the discussion agree is the low level of population growth. The size of the work force is one of the two primary factors of production in an economy’s production function, as you can see in the post The Solow-Swan Model and Where We are Economically (1). A larger work force also will demand more of the goods that it produces. Therefore, if population growth begins to slow, one can expect both supply and demand for goods and services to slow.

Most explanations for secular stagnation, however, involve free-market failures that cause too much saving and too little investment, a very venerable Keynesian meme. In the United States at least, one can demonstrate very low corporate investment, but that then begs the question of why there is such a low investment level. Is it truly a weakness of free-markets retarding investment? Or are governments repressing economic activity the fundamental cause?

Are the Keynesians Correct?

George Will’s essay on secular stagnation, in which the words “secular stagnation” do not appear, takes the form of a book review of Robert Gordon’s book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Will reviews some of the mechanisms for secular stagnation examined by the book. Toward the the end of the review, Will writes

America’s entitlement state is buckling beneath the pressure of an aging population retiring into Social Security and Medicare during chronically slow economic growth. Gordon doubts the “techno-optimists” who think exotic developments — robots, artificial intelligence, etc. — can match what such by-now-banal developments as electricity and the internal combustion engine accomplished.

That is, Gordon believes the major technological advances increasing productivity have already played out, and the kinds of advances we can expect in the future will not have even approximately the economic effect of past advances.

Finally, however, in the last two paragraphs of his book review, Will abandons neutrality toward Gordon’s ideas about secular stagnation when he writes

… there are many reasons to believe that the rapid expansion of regulatory, redistributive government, which can be reformed, has contributed to — it certainly has coincided with — the onset of (relative) economic anemia.

The “fatal conceit” (Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s term) is the optimistic delusion that planners can manage economic growth by substituting their expertise for the information generated by the billions of daily interactions of a complex market society. Gordon’s stimulating book expresses a pessimist’s fatal conceit — the belief that we know the future will be less creative than the “special century.”

This judgement by Will contains one of the primary rebuttals – perhaps even the most important one – to the argument market failures are to blame for secular stagnation; that it is government that has failed us and created this economic stagnation. A list and explanation of all the government failures retarding economic growth would fill many books, so I will content myself by listing links to my posts where they are discussed.

- The Causes of the Great Depression

- Why Did the Great Depression Last So Long?

- Causes of the 2007-2008 U.S. Financial Crisis

- Economic Effects of the Dodd-Frank Act

- The Burden of Government Regulations

- The Debilitating Effects of Obamacare

- The EPA, CO2, Mercury Emissions, and “Green” Energy

- Economic Effects of Current Tax Policy

- Economic Damage Created by the Fed

- The Rahn Curve, Hauser’s Law, the Laffer Curve and Flat Taxes

- Big Corporations Abandoning the U.S. at an Increasing Rate

The second judgement Will makes about the “fatal conceit” of central planners is also extremely important, on which I have commented in the following posts.

- Why Socialism Does Not Work

- Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” and Evolution

- Economic System States, Feedback Loops, and Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand

- Chaotic Economies and Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand

- Central Planning for Chaotic Social Systems

- How to Solve Problems in Chaotic Social Systems

I expect we are going to see a lot more economic and political discussion about secular stagnation in the future as Keynesians become increasingly embarrassed by the bad performance of Keynesian ideas.

Views: 2,567