The Law of Supply and Demand

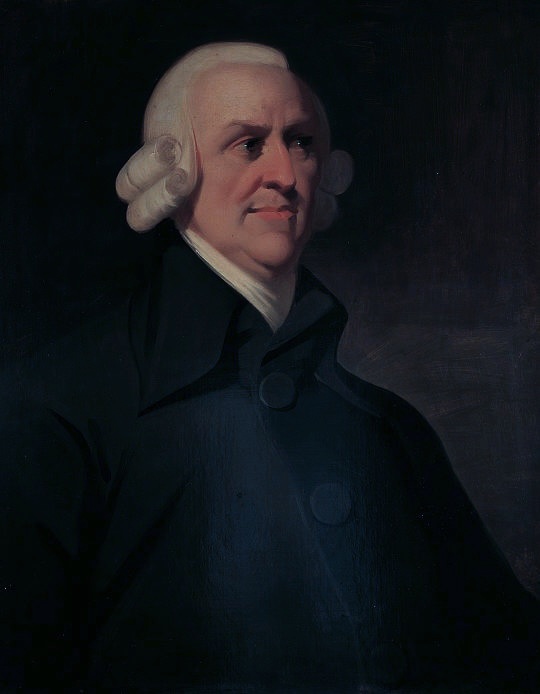

The Muir portrait of the Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith, the discoverer of the Law of Supply and Demand.

Wikimedia Commons / Scottish National Gallery

In this post I will begin to redeem my promise that I would write a separate post for each of the major neoclassical economics laws. I begin with supply and demand.

The law of supply and demand is the one economic law that everyone will recognize, at least by name. If you were to ask a random person in the street what the law of comparative advantage or the law of marginal utility were, you would probably be rewarded with a blank stare. But ask that person about supply and demand, and they might well reply: “Supply and demand? Oh, yes! That has something to do with the setting of prices.” Then again, depending on the person, you might be given that blank stare.

The law of supply and demand holds almost the same role in economics that Newton’s first two laws of motion hold in physics. It is the foundation on which the entire edifice of economic law is built. Commonly, supply and demand is attributed to Adam Smith, the Scottish moral philosopher who explained free markets in his 1776 classic An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, usually referred to as The Wealth of Nations. Parts of the law, however, were understood long before Smith by several early Muslim scholars and John Locke had a clear exposition of it in a 1691 treatise. (At least it was clear in the language of the time.) Adam Smith gave his version of it in book 1, chapter 7 of The Wealth of Nations, which was entitled Of the Natural and Market Price of Commodities. Unfortunately, the modern reader will find the language of the time rather opaque, although you can read it here should you choose.

The more usual way that a modern reader learns it is graphically through Alfred Marshall’s supply and demand curves. These curves for some arbitrary good or service, say bread loaves, will look somewhat like the diagram below.

The supply curve is labeled S in the graph while the demand curve is labeled D. The vertical axis gives the number of goods (in our case the number of bread loaves) either sold (in the case of the supply curve) or bought (in the case of the demand curve). The horizontal axis gives the price at which the good is bought and sold.

The law of supply says that the number of goods that producers are willing to produce and sell increases with the price. This seems to be an expression of common sense. If a producer can find buyers for his goods only at a very low price, he would be willing to produce only a smaller number of these goods, and would seek a more profitable way to use his remaining capital. A higher price gives the producer a greater incentive to make his good. If the maximum price he can get for the good falls below the cost of production, the number he would be willing to sell would probably fall to zero. Therefore we expect the quantity sold on the supply curve S to increase with price.

The demand curve D, on the other hand, shows that the number of goods the consumers are willing to buy decreases with price. The law of demand says that the number of goods that will be bought at a given price decreases with price. This is also a common sense statement. A consumer has a limited income, and the higher the unit price of a good, the fewer he could afford to buy. At some high price the amount that he would be willing or able to buy falls to zero.

The synthesis of the law of supply with the law of demand results in the famous law of supply and demand. The price at which the two curves intersect is called the equilibrium market price, and a moment’s consideration will show that it is a very special price indeed. At this price the quantity of the good that sellers would be willing to produce is exactly equal to the quantity that would be bought. It is the most economically efficient price in that none of the good is wasted, and no buyer will be disappointed that he cannot find enough of the good to buy. So long as the two curves do not shift relative to each other, the market will be stable and self-sustaining with the number of goods produced and sold at a given time always equal to the number bought.

So what happens when the price is set at a value that is different from the equilibrium price? Say that price is set too low at the price PL as shown in the chart above.Then the quantity of goods available for sale is less than the quantity that consumers want to be. There will be a shortage of the goods the economy would otherwise require. If the price is set above the equilibrium at the price PH in the chart above, the amount of the good that will be produced will be larger than the amount the consumers will buy. The suppliers will be left with excess goods on their hands that they will have to warehouse, and they will incur inventory costs.

Both of these kinds of price setting problems were seen in the old Soviet Union, and have also been seen in a number of cases of government price controls. For witnesses on these problems, see here and here and here. Because the law of supply and demand gives predictions that are qualitatively true as seen from historical experience, we must consider it to be in fact an economic law.

Views: 6,857