The Insanity of Negative Interest Rates

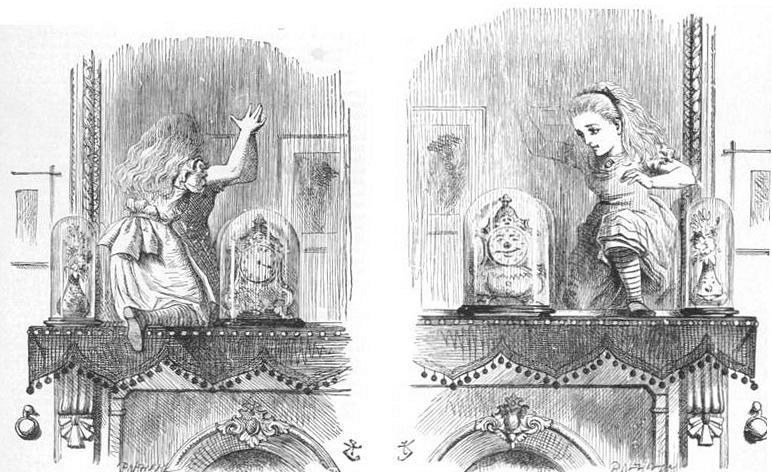

Alice entering the domain of the European Central Bank

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/John Tenniel (1820-1914) (PD-US)

Europe has now officially entered into the world of Alice in Wonderland! The European Central Bank (ECB) has jumped through the looking glass displaying negative interest rates, mirrored from what they actually should be. Because of their intimate commercial ties, three small neighbors of the Eurozone (the part of the European Community using the Euro as their currency) – Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland – have also adopted negative interest rates.

In the mad, reversed world of European banking, borrowers are paid interest for taking out loans. Savers must pay interest to banks for the privilege of parking their money with their banks.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Charles Robinson (1907) (PD-US)

The Wall Street Journal is reporting that Danish companies are paying their taxes early in order to lessen their cash at risk in bank accounts. On the other hand, Danes with adjustable rate mortgages are receiving interest payments from the banks owning their mortgages. At least someone is benefiting!

Again according to the Wall Street Journal, the ECB has decreased its deposit rate for storing excess reserves for commercial banks from negative 0.2% to negative 0.3%. That is, the ECB is charging member banks more for storing excess reserves with the ECB. In this way they expect to encourage bank loans to Eurozone businesses. Note the difference with the U.S. Federal Reserve, which pays interest for excess reserves in order to control the amount of money making its way into the economy, thereby holding inflation down.

This insanity has been provoked by the Keynesian delusion that unhealthy, stunted economies are always the result of free market failures. These failures, it is thought, induce fears among consumers and companies to shrivel aggregate economic demand. Aggregate demand is everything to a Keynesian, and a government and central bank must immediately supply it in lieu of other consumers of goods and services frightened away from the markets.

At least that is the illusion blinding the Keynesians. Yet many of the primary causes of economic crises from the Great Depression to the 2007-2008 financial crisis can be found in government actions, not free-market failures. Also, the recoveries from many of these crises have been needlessly lengthened by government actions ostensibly to get us out of trouble and restart the economy, as we have seen in the posts Why Did the Great Depression Last So Long, Economic Effects of the Dodd-Frank Act, and Economic Damage Created by the Fed. Perhaps if government did not take so many actions to stimulate the economy, emulating instead the passivity of the federal government during the 1920-1921 Depression, we would all be a lot better off. We should always be very uneasy about government’s capacity to upset supply and demand relationships throughout the economy by the unintended effects of its actions.

In addition, negative interest rates on excess reserves are inherently inflationary, since they encourage the commercial banks to take their deposits out of excess reserves and lend them to individuals and companies. This increases both the quantity and velocity of money in circulation. When combined with Quantitative Easing (QE), negative interest rates provide a potent drug cocktail for the economy, with both uppers and downers combined.

The ECB is already continuing the QE experiment run so unsuccessfully, first by Japan and then by the United States. I would be astounded if Europe did anything but repeat the bad experience of Japan and the U.S. with QE. Adding negative short-term interest rates on top of QE reinforces disincentives for savings needed for increased investments. If these disincentives reduce total investments below what is required for replacement investments (investments for replacing worn-out or obsolescent capital), then not only will Europe have failed to increase productive capacity, but its output will decline.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/John Tenniel (1871) (PD-US)

From the experience of both Japan and the U.S., QE appears to be at least mildly deflationary. This confounding aspect of QE, which superficially would seem to be inflationary since it creates such a large amount of new money, is discussed in the following posts: When QE Leads To Deflation: A Look At The “Confounding” Global Supply Glut, QE doesn’t cause inflation; it causes deflation, and for a fascinating different twist read Why Quantitative Easing (QE) May Lead to Deflation. Tommy Stubbington of the Wall Street Journal suggests the inflationary effects of negative interest rates might be expected to offset the deflationary effects of QE when he writes

In theory, negative rates at a central bank trickle down to consumers or businesses by encouraging lending. That makes cash a sort of stimulative hot potato: Everyone should want to use it, not hold it.

So far, the record has been patchy. Bank lending has risen modestly in the eurozone, aiding a slow and steady economic recovery. But inflation hasn’t returned. Prices rose just 0.1% in November. Sweden, too, has been stuck with inflation close to zero since 2013, despite joining the negative-rate club in February. The ECB has an inflation target of just under 2%.

He also notes

Denmark, by contrast, has had better success using negative rates to stabilize its currency. The rates helped beat back a flurry of speculative bets on an appreciating Danish krone, themselves spurred by the ECB’s rate-cutting moves. Growth in Denmark is comparatively robust. The economy is expected to expand 1.6% this year.

Wow! All of 1.6%! What greater recommendation can a monetary policy have? Nevertheless, I shudder to think of exactly balancing two such enormous forces against each other.

Why put your economy in such danger? As I have suggested in a different circumstance, approximately a half century of experience with monetary policies strongly suggests monetary policy is not the appropriate tool for building an economy with healthy growth. Tax cuts and enthusiastic pruning of government economic regulations would be more appropriate for that task. It would be much safer, and more efficient, to leave monetary policy only with the maintenance of the Euro’s value.

Views: 2,446