More Historical Lessons From Europe

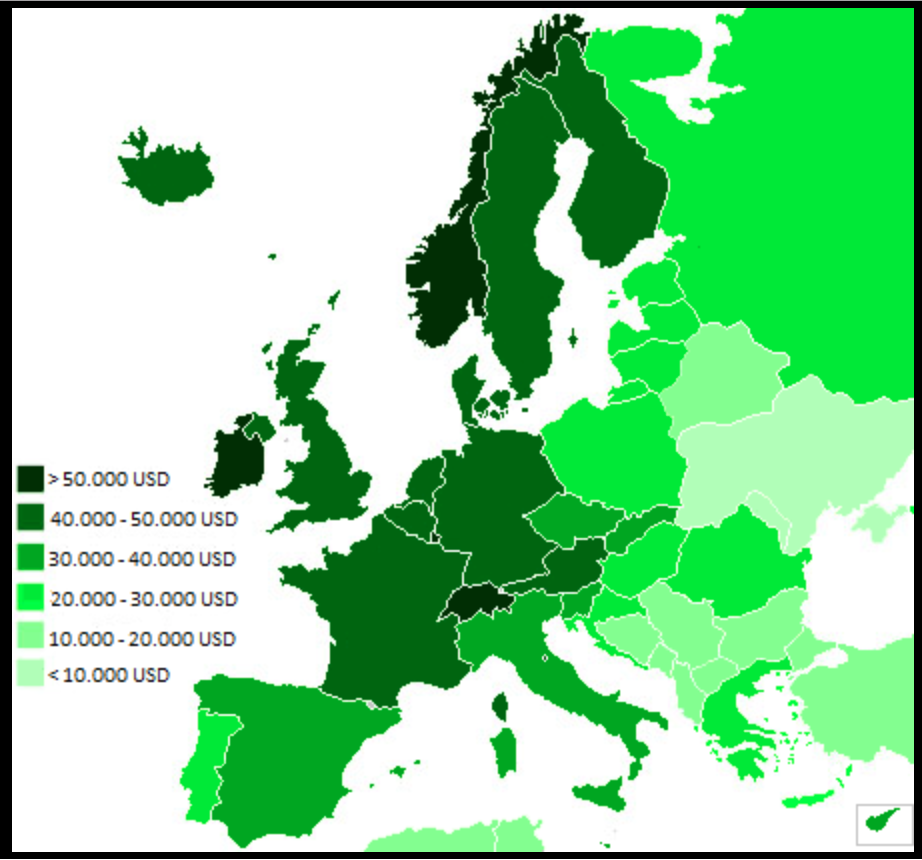

GDP per capita in Europe in 2014. According to the World Bank, the U.S. GDP per capita in the same year was $54,540.

Wikimedia Commons

In this post, I will continue my look at what history can tell us about economics and politics. In my last essay, I briefly examined what lessons the major leftist revolutions — the French Revolution and the communist revolutions of Russia and China — could give us. In this post I will investigate how the economic and political history of post-French Revolution Europe might cast a light on the current American progressive-neoliberal conversation.

Unfortunately, that conversation hardly exists, as American progressives, both in the Democratic Party and in academia, earnestly believe they have a monopoly on economic, political, and sociological truth. Why then should they bother with a conversation with neoliberals? Of coarse, progressives can point back to neoliberals such as myself and exclaim the same is true for us. And that is the problem! Both sides on this existentially important ideological battlefield are refusing to meet under a flag of truce to examine our different ideas about Reality and to see why they differ.

Let us see if we can motivate such a conversation with a look at historical lessons.

Lessons from Europe

In Europe’s modern history we can see the origins of both sides of the debate, but the actual policies adopted by governments have more often than not been dirigiste in nature. Although the idea of dirigisme is usually believed to have originated in post World War II France, the roots of French dirigisme can be found in the policies of the French Minister of Finances for King Louis XIV, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Following World War II, the French government sought to promote re-industrialization by protecting its industry from foreign competition, a distinctly mercantilist policy.

Wikimedia Commons / Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674)

This is precisely the kind of policy that Colbert developed for the Sun King. In that age all governments were mercantilist in their economic policies, and Colbert using the power of the French state did better than most in realizing them on an immense scale. What is of note here is not his implementation of the by now discredited notions of mercantilism, but his use of state power to direct the behavior of the entire French economy.

Approximately two centuries later, Otto von Bismarck, added to the repertoire of the dirigiste state. First, as Minister President of Prussia, he unified the German states into an imperial Germany through a series of engineered wars that brought them together. Then, as Chancellor of the German Empire, he coopted the Socialist Party by creating the world’s first welfare state. Although anything but a socialist himself (he seems to have regarded the Socialists as his personal enemies), he created the welfare state to gain working class support that otherwise would have gone to the Socialists.

Wikimedia Commons / German Federal Archive

It seems ironic that the creator of the German welfare state was himself entirely anti-socialist. Yet ever since the end of the French Revolution, the idea that control over the means of producing wealth (also known as “ownership”) should be taken away from private owners and given to the state had grown to be almost irresistible. In 1848, just after the Communist Manifesto had been written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, replicas of the French Revolution broke out all over Europe. Starting in Sicily and (where else?) in France, the revolutions spread over most of Europe, with apparently no cooperation or coordination between the rebellions.

The revolutions of 1848, composed of unstable coalitions of reformers, intellectuals, and common folk, did not last long. Tens of thousands lost their lives before the individual revolutions were suppressed. Yet, these revolutions were successful in popularizing ideas like liberalism (the classical kind), democracy, and socialism. Ever since, socialism has been a part of the European political environment in the many democratic-socialist and social-democratic European parties. We should note there is an actual, important distinction between democratic-socialism and social-democracy. Democratic-socialism is the belief in social ownership of the means of production within a democratic government; social-democracy is an ideology supporting government interventions in the economy to promote social justice within a capitalist economy.

Modern Europe

Virtually every European country today has its own social-democratic or democratic-socialist party, a few with more than one. Because we hear and read so much about “European socialism”, many actually think that most Western European countries are actually quasi-socialist. That was true for some of them at onetime; for example, Great Britain between 1945 and 1951 was governed by the Labour Party, a socialist party, which nationalized the healthcare industry, the coal industry, and several others. Although they lost power to the Conservatives in 1951, a continued post-war consensus allowed the nationalized industries to stay nationalized. However, that post-war consensus was shattered during the Margaret Thatcher government, after which most of the nationalized companies were privatized.

Similarly, the Scandinavian socialism about which Bernie Sanders so often rhapsodized is also becoming a thing of the past. This is the conclusion of a Swedish economist of Kurdish heritage, Nami Sanandaj in his monograph Scandinavian Unexceptconalism: Culture, Markets and the Failure of Third-Way Socialism [H7]. Published by The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in London, you can obtain it as an ebook for a modest price from Amazon, or as a free download as a PDF document from the IEA website. According to Sanandaji, the Scandinavian “third-way” radical social democratic era, with which progressives are so enamored, was in existence only between the early 1970s to the early 1990s. During this period the rate of business formation plummeted. Sanandaji states that in 2004 only 38 out of the 100 businesses with the highest revenues had begun as privately owned companies. Of that 38, only two had been started after 1970. Even more shockingly, Sanandaji writes. “Furthermore, between 1950 and 2000, although the Swedish population grew from 7 million to almost 9 million, net job creation in the private sector was close to zero.”

It was not just business formation and job creation which withered under the welfare state. The social capital, i.e. the social restraints that prohibited social welfare free-riding that had been so beneficial before the institution of the welfare state, began to deteriorate under it. Sanandaji writes,

Despite the fact that Nordic nations are characterised by good health, only the Netherlands spends more on incapacity-related unemployment than Scandinavian countries. A survey from 2001 showed that 44 per cent believed that it was acceptable to claim sickness benefits if they were dissatisfied with their working environment. Other studies have pointed to increases in sickness absence due to sporting events.

By the middle of the 1990s many Scandinavians had had enough of the welfare state, and have been episodically reducing the role of the state. During the 1990s, Sweden introduced neoliberal reforms that reduced the role of government in the economy. Taxes have been reduced and markets have been liberalized. Concerning taxes and government spending, in chapter 14 of his monograph, Sanandaji writes,

Since the 1980s, there has been a tentative return to free markets. In education in Sweden, parental choice has been promoted. There has also been reform to pensions systems, sickness benefits and labour market regulations, though the precise nature of reforms varies between countries. … Furthermore, the level of taxation and government spending in Scandinavian countries, though still high by historical and international standards, is no longer significantly higher than other EU countries. Economic freedom has increased in Scandinavia more rapidly than in most other developed countries and the relative decline of Scandinavian living standards has now been reversed.

Also the social democratic parties that had introduced the welfare state seem to be losing their hold on government. In June, 2015, the Danish Prime Minister and head of the Social Democrats, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, lost her seat in the Danish Parliament and her party lost power to the center-right Venstre party. That left Sweden as the only Scandinavian government still in Social Democrat hands.

Nevertheless, although the examples of European democratic-socialist regimes are becoming fewer, most European countries are still social-democracies to one degree or another. If the progressive view of Reality is correct, we would expect most of Europe to be doing better economically than the U.S. However, if we live in a neoliberal universe, we would expect most of Europe to be doing just as poorly (the U.S. is not even close to being a paragon of free-markets!) or worse than the United States. So what do the data tell us?

If you look at the “heat map” at the top of this post showing the GDP per capita of European countries in 2014, you would see that most European countries have smaller GDP per capita than the U.S. The exceptions are Norway and Ireland, as you can see in the plot shown below.

Data Source: the World Bank

The better performance of Norway and Ireland will be discussed shortly. For now, however, let us consider the other Western European countries, beginning with the Northern European countries reputed to have better economies than the Southern European countries. Their GDP per capita from 1980 to 2015 is shown below.

Data Source: the World Bank

Clearly, the U.S. has outperformed the major northern European nations in most years since 2000 with the exception of Ireland. Ireland is the only country in the set excepting the U.S. that still has a growing economy. Their growth rates over the time period are plotted below.

Data Source: the World Bank

Currently, the only country that stands out from the pack is Ireland, with most other countries having low or negative growth rates.

Next, consider the major southern European nations that are not doing so well as their northern brethren. First is the plot of their per capita GDP.

Data Source: the World Bank

Not only are they doing considerably worse than the northern tier of countries, they have not even recovered from the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Next, let us take a look at the GDP per capita of the three major Scandinavian countries.

Data Source: the World Bank

Currently, the GDP for all three nations is falling, although that for Norway is still considerable above the U.S.

Next, consider the unemployment rates of Western Europe, as displayed in the heat map below.

Wikimedia Commons / Heycci

With the exception of the countries colored green (Norway, Germany, and the Czech Republic), all the other countries are getting hammered with unemployment.

All of this data suggests a region of the world that is mostly in deep, serious economic trouble. The U.S. itself is in serious economic trouble, as I note in the posts Dismal Economic Numbers, Why Isn’t the US Economy Booming?, and Perspectives on Unemployment. Yet all the data illustrated in the plots above suggests that most of Europe, with two major exceptions, is in even worse shape than the United States.

This observation should not be too surprising if we are living in the world of the neoliberals, rather than that of the progressives. From the neoliberal point of view, what we are seeing now in the U.S. is the accumulation over many decades of increasing federal government interference with the economy. Most Western European countries are simply approaching the same endpoint faster, and for the same reasons.

The European Exceptions: Norway and Ireland

What screams out for explanation in this general picture of Europe is just why Norway and Ireland are doing so much better than either the United States or the rest of Europe. There are plenty of reasons why the U.S. and the rest of Europe are doing so poorly, but what are Norway’s and Ireland’s explanation(s) for their better growth?

First, let us consider Norway, which is the most confusing of the two European outliers. The first thing to be noted is Norway and the U.S. are actually fairly close to each other in economic freedom as measured by the Heritage Foundation/WSJ index of economic freedom for 2017. Norway has an index of 74.0, while the U.S. has 75.1. Yet, looking at figure 1 and comparing it to figures 2 and 4, we can see Norway has had far better GDP per capita growth than the U.S. or any other country of Europe starting around the year 2001. For Norway’s growth to be so much better than the U.S.’s suggests that some of the component factors of the index of economic freedom should be more heavily weighted than others, rather than equally weighted as in the current index. Some types of economic freedom appear to be more important than others.

As discussed above, starting in the late 1990s, all of the Scandinavian countries introduced reforms to move them away from socialism and to lessen the weight of the welfare state. Yet, Norway must have found some reforms that boosted their GDP much more than the GDPs of Sweden and Denmark.

If we compare the economic freedom index and its component factors versus those of the United States, we find significant differences in factors measuring the rule of law and government size, with most of the differences favoring Norway. Concerning Norway’s superior values for the rule of law, the Heritage Foundation states:

Private property rights are securely protected, and commercial contracts are reliably enforced. The judiciary is independent, and the court system operates fairly at the local and national levels. Norway is one of the world’s least corrupt countries and is ranked fifth out of 168 countries in Transparency International’s 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index. Well-established anticorruption measures reinforce a cultural emphasis on government integrity.

On the other hand, concerning the rule of law in the United States, the Heritage Foundation is considerably less effusive in its judgements.

Although property rights are guaranteed and the judiciary functions independently and predictably, protection of property rights has been uneven. For example, rising civil asset forfeitures by law enforcement agencies and a vast expansion of occupational licensing have directly encroached on U.S. citizens’ property rights. The Pew Research Center reported in late 2015 that just 19 percent of Americans trust the government always or most of the time.

It is easy to imagine how these differences all by themselves could account for the superior GDP growth of Norway.

Looking at those factors and sub factors concerning government size, one’s first impression is progressives might have a point that larger government can be conducive for higher growth rates. However, looking at the factors more closely, we can see the situation is more complicated than first impressions imply. The major factors and their values for Norway and the U.S. are:

- Norway

- Government Spending: 38.5

- Government spending averaged 45.3% of GDP over the past three years

- Tax Burden: 55.6

- Top personal income tax rate: 47.8%

- Top corporate tax rate: 25%

- Overall tax burden: 39.1% of GDP

- Fiscal Health: 98.4

- Budget surpluses have averaged 8.1% of GDP over past three years

- Public debt is 27.9% of GDP

- Government Spending: 38.5

- United States

- Government Spending: 55.9

- Government spending averaged 38.3% of GDP over the past three years

- Tax Burden: 65.3

- Top personal income tax rate: 39.6%

- Top corporate tax rate: 35%

- Overall tax burden: 26.0% of GDP

- Fiscal Health: 53.3

- Federal budget deficits have averaged 4.1% of GDP over the past three years

- Public debt is 105.8% of GDP

- Government Spending: 55.9

I should note in passing that the higher a factor’s score, the less the government impacts the economy. This means the higher the score for government spending, the less the government spends as a share of GDP. Also, the higher the tax burden score, the less the government burdens the economy with taxes; the higher the fiscal health score, the less the government burdens the country with the financing of the public debt.

A progressive will look at this data and immediately conclude that Norway’s higher growth rates are related to the fact Norway is a higher taxed and higher spending country than the U.S. However, if you look closely, you will see that Norway immediately pays for all expenditures and still ends up with a surplus of around 8.1% of GDP. By contrast, the United States pays out all the year’s revenues in expenditures, but still must finance annual deficits that have averaged 4.1% over the past three years. As a result of all this, the U.S. national debt is 105.8% of GDP, while Norway’s national debt is only 27.9% of its GDP. The import of this fact is that the higher the national debt as a share of GDP, the more the central government must take from the country’s savings by selling bonds, and the smaller the fraction of savings is left over for investments by companies in the economy’s productive capacity. We know from the researches of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff that anytime sovereign debt exceeds about roughly 80% to 90% of GDP, government borrowing to finance deficit spending begins to crowd companies out of financial markets and begins to kill private investment.

Also, note this about the U.S. budget deficits. If you take the 4.1% of GDP the federal government must borrow to finance the yearly deficit and add it to the 26% of GDP that total taxes bring in, you get a total government financial burden of 30.1% of GDP, which is considerably closer to the total Norwegian tax burden of 39.1%.

However, the preceding comments are not the total story. Just as important as the total amount taken from the GDP in taxes is from where the state takes the taxes. In Norway the top corporate tax rate is an astoundingly low 25%, whereas the top American corporate tax rate is 35%, the highest corporate tax rate in the world except for the African country of Chad. Such high American corporate taxes often make U.S. companies uncompetitive with foreign companies, not only overseas but also in the U.S. domestic markets. Not only that, but they reduce the amount of a company’s assets available for investment.

Progressives will often respond to these observations on corporate taxes by saying that companies do not usually pay a 35% tax rate due to various tax deductions, credits, and exemptions. However, these tax breaks are not uniform over all industries, or even over all companies in a single industry. Below is a bar chart showing average tax rates in some selected industries using data from New York University professor of finance Aswath Damodaran. The chart takes into account the tax breaks available.

Investopedia / NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran

These corporate tax breaks are an essential fuel for crony capitalism, and by favoring one industry over another are themselves a major cause of economic harm. By artificially limiting the cost of some goods, they distort the economic signals about the relative availability of the goods involved.

Another advantage Norway has over the United States in international trade is the territorial tax system their companies enjoy, while the United States imposes a world-wide tax system. Norway taxes companies only once for profits earned on Norwegian territory, while U.S. multinationals are taxed twice, once by the government of the country where the profit was earned, and once by the U.S. government when the profits are brought back to the United States. If a U.S. company is taxed 20% by the government in the country where it is earned and then taxed an effective rate of 15% (taking the overseas tax as a deduction), then the U.S. company pays a total tax of 35% on its overseas profit.

The comments above may or may not be the total explanation for the superior Norwegian performance over that of the United States, but it is quite clear the better performance is not due to higher tax burdens. Taxes are everywhere and always destructive of what is taxed. No truer truism was ever uttered than you will always get less of whatever is taxed.

By comparison, the explanation for Ireland’s better performance is much easier. To begin with, Ireland has more economic freedom than the United States according to the index of economic freedom. Ireland’s score is 76.7, while that of the U.S. is 75.1. All of the factors for Ireland concerning the rule of law are approximately the same or better than those of the United States. Almost all of the factors concerning government size favor Ireland over the U.S, and are compared below:

- Ireland

- Government Spending: 57.1

- Government spending averaged 37.8% of GDP over the past three years

- Tax Burden: 72.7

- Top personal income tax rate: 41%

- Top corporate tax rate: 12.5%

- Overall tax burden: 29.9% of GDP

- Fiscal Health: 60.3

- Budget deficits have averaged 3.7% of GDP over past three years

- Public debt is 78.7% of GDP

- United States

- Government Spending: 55.9

- Government spending averaged 38.3% of GDP over the past three years

- Tax Burden: 65.3

- Top personal income tax rate: 39.6%

- Top corporate tax rate: 35%

- Overall tax burden: 26.0% of GDP

- Fiscal Health: 53.3

- Federal budget deficits have averaged 4.1% of GDP over the past three years

- Public debt is 105.8% of GDP

- Government Spending: 55.9

Although the Irish overall tax burden is slightly higher than that of the U.S., 29.9% of GDP versus 26.0% for the U.S., all of the comments on lower corporate tax rates are even more true here. Ireland has a very diminutive top corporate rate of 12.5%, complimented with a territorial tax system. There is absolutely no surprise that many American multinationals fleeing the United States for a more economically hospitable new country have fled to Ireland for their new home!

Summing Up

Just like the United States, most of Europe is deteriorating economically with time. Although the details behind the various decaying economies are different, the fundamental cause is the same: The unbounded faith of these nations’ elites in the capability of government to manage and control both their societies and economies. Not knowing that human systems are intrinsically chaotic, with their behavior fundamentally determined between pairs of individuals and/or relatively small groups of individuals, governments are like bulls in a china shop when they try to stimulate economic activity.

We appear to be at a point in history when we need a paradigm shift in how classically liberal countries rule themselves. Dirigisme no longer works. What replaces it?

Views: 3,300