Historical Lessons on Economics and Politics

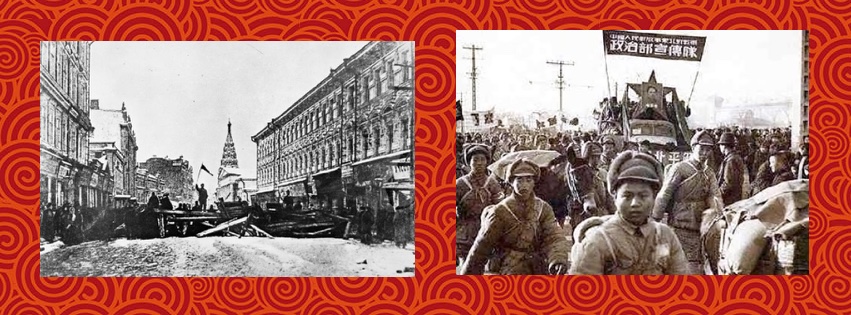

Revolutionary Images: Lessons to be avoided like the plague!

Left: A barricade erected by revolutionaries in Moscow, 1905. Wikimedia Commons / Imperial War Museum

Right: People’s Liberation Army entering Beijing, 1949. Socialist Worker

How to further the conversation between progressives and neoliberals? That was the the question I left with you at the end of my last post. The fact we desperately need such a conversation is underlined by the almost hysterical reaction of the American Left to the election of Donald Trump. From their reaction, one would think Trump is one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Either that or he is merely a Russian agent.

A Desperate Need to Talk to Each Other

If we can not talk to each other, with the way hatred and contempt is being stoked in both of the two major American ideological groups, we might well be facing each other in a second American Civil War. The conversations we need should not be about values and ethics, as both hostile adversaries possess the same basic ethical and social values. Instead, they should be about what

Wikimedia Commons / Viktor Vasnetsov (1887)

really divides us, which is our beliefs about what Reality actually allows us to do to fulfill what we all desire for our country. That is what our differing ideologies provide us.

Since our basic arguments are about the nature of Reality, our discussions should be dominated by data, and what that data tells us about how Reality is actually organized. Some aspects of this conversation will be long-term, as I reluctantly concluded in my last essay. The issue in that case was about how taxes really affected society, and the data did not unambiguously settle the question the way I had hoped. The effects of taxes on society are many, sometimes subtle, and often complicated. I expect the American Left and Right will be arguing about them for a long, long time.

One way to wage ideological combat with data is to access the many databases freely accessible on the internet. Among these are the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED), the World Bank, and the European Union’s Eurostat database. While I will continue using these and other sources of basic data in future essays, in this essay I will use data from that record of human experiences we call history. Let us see if appeals to the historical record can advance the conversation.

Historical Lessons of the Revolutionary Left

Let us begin with some history about the Revolutionary Left. I suspect most American progressives would consider this to be a rhetorical softball, as there are few American defenders of the methods and results of the Revolutionary Left. There are three major leftist revolutions to be examined: The French Revolution (1789-1799), the Russian Revolution (1905-1907), and the Chinese Revolution (1946-1950).

The French Revolution, the prototype of them all, was sparked by several causes. To begin with, the French government was deeply in debt arising from their participation in the Seven Years’ War (1754-1763), known as the French and Indian War in the English American colonies, and in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Responding to this debt, the French government instituted a number of unpopular taxation policies. Compounding with the effects of unpopular taxes were years of bad harvests that inflamed peasant and commoner anger toward the feudal privileges of the church and the aristocracy. On top of all this, the political ideals of the Age of Enlightenment were informing noble and commoner alike that power to rule was delivered by the consent of the governed; that once the social contract between ruler and ruled was violated, the ruled could replace their rulers.

Finally this volatile witches’ brew boiled over in 1789 into actual revolution with abolition of the rules of feudalism. These rules provided seigneurial rights for the nobility and rights to tithes for the Roman Catholic Church. The history of the French Revolution is a fascinating, complex event that completely buried what was left of medieval Europe, ushering in the modern era. I can not even begin to scratch the surface of all the developments and their implications arising from the French Revolution. Nevertheless, should your interest be piqued, two books I have found useful are The Days of the French Revolution by Christopher Hibbert [H9], and The Age of Napoleon by J, Christopher Herold [H10].

During the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror, France under the Committee of Public Safety displayed a characteristic common to all the leftist revolutions: Eventually, they all began to kill their own people. Under the Reign of Terror it has been estimated more than 17,000 lives were lost to Madame Guillotine. In order

Wikimedia Commons / Unknown artist

to accomplish all this, the Committee of Public Safety had to assume dictatorial powers, another common characteristic of leftist revolutions. Because of their bloody rule, the Committee of Public Safety was overthrown and replaced by another dictatorial organization called the Directory. Fittingly, the leader of the Committee of Public Safety, Maximillian Robespierre, and 21 other members of the Committee were guillotined without trial in the Place de la Revolution. The Directory in its turn was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte, who became the dictatorial First Consul of France and eventually the French emperor.

It is very telling, I believe, that every single historical leftist revolution has ended up with an authoritarian government.

The Lessons from the Communist Revolution of Russia

The first thing to note about the communist revolutions of Russia and China is that they too instituted dictatorial governments. The second point is that just like revolutionary France, the Soviet Union and China were not only oppressive, but they killed a great many of their own people to eliminate any dissent. It is estimated 94 million were killed in the communist nations of China, the Soviet Union, North Korea, Eastern Europe, and Afghanistan in the 20th century.

The third important point is just how spectacularly bad the communists were in managing their economies. For example, for Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand to function, not only do the laws of supply and demand and of marginal utility have to work, but also a free-market must exist to allow the quantity-price point to be pushed to the equilibrium market price. The natural working of supply and demand and of marginal utility are pretty much culturally independent, depending only on the existence of an economy in which goods and services are exchanged.

In the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics there was a rich history of what the law of supply and demand did to that state when the commissars set prices quite differently from the market equilibrium. Consumer prices like the price of bread were often set low causing massive shortages. Occasionally, prices

Photo Credit: Reddit / HistoryPorn

for industrial goods were set high, causing large surpluses that had to be warehoused. But while the law of supply and demand and the law of marginal utility continued to work in the Soviet Union, one essential part of the invisible hand was absent. There was no free-market to cause the setting of the market price. Once the Soviet Union took over Eastern Europe, this socialist disease of everlasting shortages and surpluses (depending on the good) was exported to the Soviet Union’s new vassal states.

Everything considered given its dysfunctional economy, the Soviet Union lasted a very long time from 1922 until 1991, a little more than two-thirds of a century. Although much has been made of the economic pressure placed on it by the West, I suspect much of the reason for its final dissolution had as much to do with the communists simply ceasing to believe in their own ideology.

Before passing on to a few remarks about China, there is one more rather remarkable observation to be made of the Soviet Union. The masters and economists of the Soviet Union knew the basic neoclassical laws of economics, especially supply and demand and the law of marginal utility, were just as valid within their socialist country as in any other country. However, they also knew that because they insisted on having total control of prices and wages, the automatic flexibility of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand in the optimal setting of quantities and prices of goods was denied them. Nevertheless, no less than any profit-seeking capitalist, they also wanted to avoid the economy-destroying inefficiencies of shortages and surpluses. As a result they made the only serious attempt in history to replace free-markets and yet maintain its function of setting the market prices and quantities produced for the various goods.

That attempt was the idea of market socialism developed by the Polish economist Oskar Lange. With his system, prices for goods would be set by a government board and then adjusted according to whether a surplus or a shortage was produced. The Soviet Union adopted this method for setting prices and tried mightily to make it succeed. Unfortunately for the Soviet Union and its empire, it never worked. One large problem was probably the huge scale of the number of prices that needed to be set together with the finite time a relatively small board would have to set the prices. In a free-market prices are set by a large number of companies and merchants, who as a work force number in the many millions in the United States. (In 2010 there were 27.9 million small businesses in the U.S. In each business there would be at least one individual responsible for setting their prices, and for many businesses there would be several.) Even if a socialist price-fixing board had a work force in the thousands, it would be difficult for it to cover all prices in the economy over a realistic time-period. At any rate we know empirically that the effort failed because of the large number of shortages and surpluses that came out of the Soviet Union. I know of no other serious attempt to replace the functioning of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. Economies without free-markets simply will not and can not perform well in the sense of balancing demand with supply.

Lessons from China

The lessons learned from communist China’s historical experience are, as you might expect, very similar to those from the Soviet Union. The one new aspect was provided following the dissolution of the Soviet Union by an attempt to move China away from state socialism to a kind of “state capitalism”. The beginning phase of that move in 1976 actually predated the fall of the Soviet Union, but was a seed that did not flower until the late 1990s. In that year Mao’s designated successor, Hua Guofeng, started a program of economic modernization that was a state-driven scheme for industrialization. Hua and his program did not last long. In early 1979 his program was canceled because of its own defects, and Hua himself was replaced by Deng Xiaoping. Deng in turn appointed a shadowy figure named Chen Yun as the top Chinese official in charge of economic affairs. Chen was also a modernizer and a strong believer in central planning.

What Chen realized was that the Chinese economy had created and had long suffered from a structural imbalance with heavy industry favored over light industry and agriculture. Hua’s previous program to develop heavy industry was exactly the wrong prescription for the ailing economy, but it did get officials like Chen to think about what would be better. To right the imbalance, Chen started a two part round of economic reform. The first piece involved an adjustment of the overweight industrial sector, with the second part being a state-enterprise reform at the microeconomic level. More economic assets were allocated to consumer goods and agriculture. The government also decentralized foreign trade, giving provincial governments more freedom to make economic decisions. In addition, more power was devolved to state-owned enterprises, allowing them to keep some profits and decide on how they would be reinvested.

Once power was taken away from the central government, local governments and private individuals were more than happy to take what was offered and to appropriate as much more at the margins as the central government allowed. Although these marginal economic agents were acting outside the boundaries of socialism, Beijing was more than content to leave them alone, so long as they did not threaten state-owned companies or, even more important, did not endanger the primacy of the Communist Party.

This is the first lesson from the Chinese experience. Economies naturally operate best when the most important economic decisions about allocating economic resources are made privately by the companies that supply and the consumers who buy goods. The supply-demand balances on which the health of the economy depends are most easily created and maintained at the microeconomic level. As a result, any authoritarian government showing even the slightest tendency to devolve economic power to local and private players is likely to see power ripped away from them to be relocated in the private sector. This is exactly what happen to China. The emergence of private companies and stock markets actually occurred before the party approved them, with the Shanghai Stock Exchange opening to exchange company stocks and bonds in November-December 1990. In 2004 China changed its constitution to allow private-property rights, and in 2007 a new property law was enacted to make practical the realization of those rights.

China was showing every promise of evolving into a capitalist country, with China joining the World Trade Organization in December 2001. The Chinese were rewarded for their moves away from socialism with high and sustained economic growth beginning with 14.2% in 1992. There had been episodic growth before then, but it was fitful and followed by crashes or periods of low growth not characteristic of an economically underdeveloped nation. From 1989 to 2016 its growth averaged 9.76 percent.

However, the siren song of government power is also a powerful force, and one the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party could not resist. They have retained absolute power over their economy by reserving the right to control investments. Capital allocation is a rather murky affair in China, with the Chinese government trying to direct capital flows through state-owned investment banks. It should be no surprise then that a great deal of wasted malinvestment of scarce Chinese economic resources were made. Approximately $6.8 trillions worth of waste. That is the amount estimated in a joint report by China’s National Development and Reform Commission and the Academy of Macroeconomic Research. That is about 40% of the U.S. GDP and two years of output for the entire German nation. This horrendous quantity of waste is approximately half of all Chinese investment in the years covered by the report between 2009 and 2013. Some of that bad investment went to build ghost cities, cities essentially without any population! It is no wonder the Chinese economy is currently crashing.

This leads to our final lesson from the leftist revolutions. Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom is more like the Highway to Serfdom. Even though the devolvement of economic power to local, private hands was very powerful in China and very rewarding for China, the lust for absolute power was just too much for China’s masters. We should all remember to beware the giving of any power, but particularly economic power, to the government. To present such gifts is not only a threat to your pocketbook, but to your very freedoms as well.

In my next post, I will search for historical lessons from Europe and the economically developing nations.

Views: 2,849