Feedback Loops and Economic System States

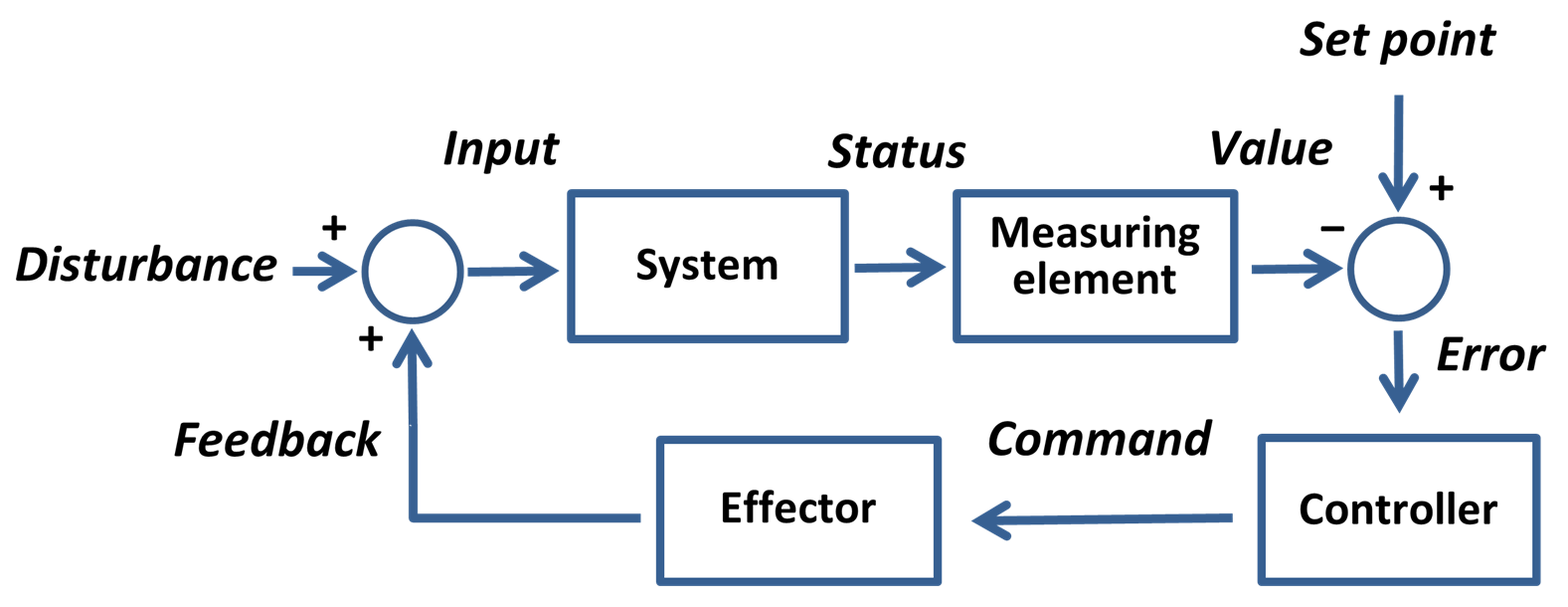

Organization of a feedback loop Wikimedia Commons/Brews ohare – Own work

My friend Chease has again proposed I consider a very interesting article concerning Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand”. Last August he suggested the post Is Economics Built on A “Monumental Mistake?” by Jag Bhalla demonstrated Adam Smith’s invisible hand would need the flexibility of the biological process of evolution to do its job, and that the invisible hand did not make the grade to explain systematically good economic outcomes. In that post the discussion was motivated by the following paragraph in the book Does Altruism Exist?: Culture, Genes, and the Welfare of Others. by the eminent biologist Davis Sloan Wilson.

Large societies function well, to the extent that they do, only thanks to proximate mechanisms that evolved by cultural evolution and that interface with our genetically evolved mechanisms. We know about some of these mechanisms, especially those that we intentionally designed in our conscious efforts to improve the welfare of society (e.g., laws and constitutions). But large societies function well in part because of mechanisms that no one planned or intended, but that nevertheless caused some groups to outcompete other groups. This gives large societies an invisible-hand-like quality, as noted by early thinkers such as Bernard Mandeville and Adam Smith, but it was a monumental mistake to conclude that something as complex as a large society can self-organize on the basis of individual greed.

The emphasis in the last sentence is my own, put there to highlight the point of contention. My response in Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” and Evolution was that Sloan misinterpreted the nature of the invisible hand. The invisible hand has all the functionality of biological evolution built into it, possessing aspects of both mutation and natural selection.

Apparently not persuaded, Chease asked in a comment to Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” and Evolution that I consider the paper Exploring the concept of homeostasis and considering its implications for economics by Antonio Damasio and Hanna Damasio, published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. Biological homeostasis refers to the ability of biological regulatory systems to use feedbacks using chemical and neurological messages to regulate critical quantities such as body temperature and glucose levels. The Damasios suggest a society’s economy is an analogue for the collection of homeostatic systems in the body of a biological organism. They propose that if they extend the concept of a biological homeostatic system to include conscious thought, they can include the economy as part of humanity’s homeostatic systems. They write in their abstract

Our goal here is to consider a more comprehensive view of homeostasis. This includes its application to systems in which the presence of conscious and deliberative minds, individually and in social groups, permits the creation of supplementary regulatory mechanisms aimed at achieving balanced and thus survivable life states but more prone to failure than the fully automated mechanisms. We suggest that an economy is an example of one such regulatory mechanism, and that facts regarding human homeostasis may be of value in the study of economic problems. Importantly, the reality of human homeostasis expands the views on preferences and rational choice that are part of traditionally conceived Homo economicus and casts doubts on economic models that depend only on an “invisible hand” mechanism.

Consider an organism’s problem of obtaining sufficient energy to continue living. Glucose levels fall and chemically induced messages to the brain inform the organism that it is hungry. The organism feels hunger. If the organism is a higher, more evolved animal such as a wolf or a man, the feeling of hunger induces thoughts in the animal to hunt for food. Hence both feelings and conscious thoughts are part of the homeostatic systems controlling glucose levels in the blood stream. The Damasios observe how the addition of conscious thinking to a homeostatic system opens the possibility of errors in thinking that damages the working of the system. In their words, “… the conscious/feeling variety of homeostatic regulation is far more prone to malfunction than the plain, automatic version. This is because it offers too much freedom of operation. It allows the organism’s owner to make non-preprogrammed choices and those choices may, immediately or over time, be in conflict with or even counter the main homeostatic goals.” However, the mind of the human animal is a wonderfully dexterous and inventive tool for solving humans’ problems, and human technology and social institutions are regarded by the Damasios as an extension of human homeostatic systems. Homeostatic systems including social institutions help humans to take in signals from the world on problems. They then provide feedback to regulate or modify the world to maintain a state of survival and greater well-being. The Damasios call such examples of homeostasis sociocultural homeostasis. Concerning the functions of sociocultural homeostasis, they write,

From the perspective of life regulation all the devices of sociocultural homeostasis appear to have their origin in an identified need. They all aim at a goal compatible with both survival and a state of well-being. In other words, states of physical equilibrium or of neutral balance do not appear sufficient. An up-regulation toward well-being is easily identifiable as a general human goal.

One might quibble with the Damasios about whether they are stretching the notion of homeostasis a bit too far by straying beyond the biological and from the internal self-regulation of one individual to that of many individuals. The one feature uniting biological homeostasis with the notion of sociocultural homeostasis is that of feedback mechanisms for regulating the system’s state. However, homeostasis is as good a word as any other to label a process of self-regulation, and perhaps other examples of biological homeostasis such as the action of immune systems might provide fruitful ideas about social organizations. So, let us listen to what they have to say about economies as sociocultural homeostatic systems in general, and about Adam Smith’s invisible hand in particular.

Concerning the effects of cultural values, feelings, and ideas on economies, they write

For example, the notion of humans as exclusively self-interested in terms of means and goals, is closer to fiction than reality. In this regard, the assumptions most at odds with current biological views include the notion of preferences that would be stable and impervious to the varied social factors that seem to have a major bearing on all sorts of economic decisions. Social phenomena have had a large influence on the evolution of the processes of affect, and the latter exert a huge influence on the matter of preferences and the calculation of utility. Feelings, in all their variety, intensity, and valence, exert powerful influences on economic preferences (intriguingly, the concepts behind terms such as “preferences” and “utility” in the vocabulary of economics, can be related to terms used in the biology of homeostasis such as “need” and “reward”). Varied degrees of cooperation of kin and non-kin, regulation of in-group and out-group behavior, social emotions, along with climate and geography, have generated varied historical paths and thus varied cultures. Such cultures, as George Ackerlof has suggested, impose separate socio-cultural identities (Akerlof and Kranton, 2010). Economic models which ignore the role of socio-cultural identities and their attendant affective profiles are not likely to reflect reality.

Finally, here is the Damasios’ appreciation of Adam Smith’s invisible hand.

Because there is a dual nature to human homeostatic control, and because conscious deliberation is a patent human reality, it is not likely that economic systems operating [Sic] well only on the basis of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” ( Smith, 1776). The invisible hand idea fits well the homeostatic world of bacterial cells, an un-minded world in which quorum sensing accomplishes a lot of good governance and is indeed invisible. But the invisible hand does not capture fully to the human case. The wide variety of cultural instruments that human conscious feelingness and intellect have created, are subject to their own cultural evolution. The responses they generate may or may not coincide with those that the evolutionarily older invisible hand devices would produce.

Here is where I definitely disagree with the Damasios. The “dual nature to human homeostatic control” they refer to is the action of both thoughts and feelings/values, which being different in different cultures, cause different economic demands and ways of organizing supply to meet those demands. They consider the invisible hand to be too dumb an instrument to take account of these differences; or more accurately, they believe the invisible hand to be too adapted to free-market economies to be able necessarily to work in other cultures.

Before I register my detailed dissent on this view of the operation of the invisible hand, let us review just what the invisible hand is. Adam Smith in book IV, chapter II of his classic work An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations writes how suppliers of goods meet the needs of consumers.

As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can, both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce maybe of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. … by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain; and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

The emphasis in the quote is mine. How are we to understand this ‘invisible hand’ in terms of modern day understandings of economics? I will write about this and my detailed dissent from the Damasios in my next post.

Views: 3,850