Does An Inverted Yield Curve Predict U.S. Recession?

Some U.S. Treasury yield curves have become inverted. This means the yield of a long-term Treasury bond (say the 10-year Treasury) is less than the yield of a short-term bond. The short-term yield people usually talk about is that of the 2-year bond, although yield spreads from 3-month bonds are also of note.

For a very long time, an inverted yield curve usually has preceded a recession within 24 months. Should we begin to worry, or are there explanations for the inverted yield curve other than an imminent recession?

Bond Prices and Yields

When a person buys stock in a company and the company does well, quite often the stock price and dividends from the company both go up together. This situation is quite different from bonds, whether the bonds are sold by a company or by governments. For bonds, the analog of stock dividends is the bond’s yield. A bond’s yield is its annual interest payment (its “coupon” payment) divided by what the bond’s owner paid for it.

The bond is a debt to the bondholder from the issuer of the bond, whether company or government. The bond’s issuer promises to pay back the initial value of each bond over a specified period, called the maturation period, plus some interest. After that, paybacks from the bond issuer cease. Usually, the constant payback is by quarter, with the quarterly payback being the price divided by the number of quarters in the maturation period plus the interest for that quarterly period. This quarterly return remains constant, from quarter to quarter.

If the bonds are resold, as they often are, the return on each bond remains unchanged. If the buyer buys at a different price, then the buyer’s actual percent return or yield from the bond is that constant return divided by the price at which he/she bought each bond. If the price of each bond is higher, the bond’s yield is lower; if each bond’s price is lower, its yield is higher. Therefore, there is always an inverse relationship between a bond’s price and its yield.

What an Inverted Yield Curve Is, and Why It Might Mean Trouble

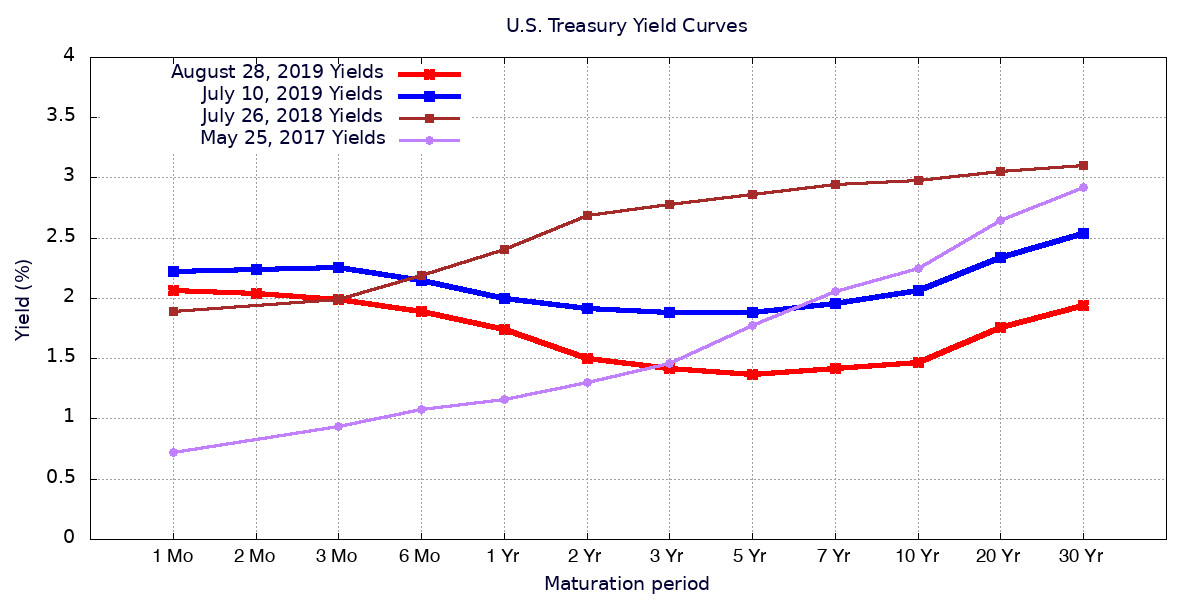

A yield curve for a bond is its yield as a function of its maturation period. Usually, the yield is quoted as a percentage yield, which is the fractional yield (constant return per bond divided by its price) times 100%. This yield varies with time as the bond’s price changes. You can see U.S. Treasury bond yield curves for four different dates in this post’s theme image above.

Now, in healthy economic times when the economy is growing robustly, buyers of bonds will demand higher returns (yields) from long-term maturation bonds than from short-term bonds. Since longer maturations provide greater risks for the investor, investors will require greater yields as the maturation period increases. In the theme image, the purple yield curve for May 25, 2017, and the brown curve for July 26, 2018 are the kinds of curves we would expect for a healthy economy. However, the curves for July 10, 2019, and August 28, 2019, show the yields for many longer maturation period bonds as smaller than the yields of shorter maturation bonds. These are “inverted yield curves.” What explains them?

Another way of looking at inverted yields is to take the difference in yield between a longer maturation bond and some specified short-term bond. This is called a bond spread. As long as the spread is positive, there is no yield inversion. In the figure below, we plot the yield spread between Treasury bonds of longer maturation and two year Treasury bonds as a function of time.

Data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury

Note how the spreads have grown progressively smaller over the past two years. In particular, observe how the spread between the ten year and two-year treasuries has just become negative, indicating yield curve inversion. This is what has triggered the hullabaloo in the news media and among pundits about the possibility of an imminent recession.

Sometimes people like to look at the spread between three-month treasuries and the longer treasuries. Some of these yield spread curves are shown below. Clearly, they are more emphatic about bond yield inversion.

Data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury

So just why should we think these bond yield inversions prophesy a recession within 24 months? First of all, there is the empirical historical experience, as shown in the plot below.

Federal Reserve District Bank of Chicago / Benzoni, Chyruk, and Kelley

As you can see from the plot, every recession since the 1970s was preceded by a bond yield inversion not more than two years before. However, this strong correlation is not always prophetic. Note the bond yield inversion in the mid-1960s that briefly vanished before the relatively mild recession in 1970.

What follows is the conventional explanation for bond yield inversions shortly prior to a recession. As economic conditions deteriorate, investors become anxious about the safety of their investments, particularly in corporate stocks. They then sell their stocks and put that capital into the relative safety of bonds, especially federal government treasuries. Because they expect problems in the short-term, they look for higher returns, which they find more in the non-inverted long-term bonds than in short-term bonds. Panicked investors then pile their precious capital into longer-term treasuries. As the demand for these long-term bonds increases, their prices increase. As their prices increase, their yields decrease. In the meantime, the prices and yields for shorter-term bonds do not change as much. The result is the bond yield curve inversion.

However, that is not the only explanation for our current yield curve inversion.

A More Probable Alternative Explanation for Bond Yield Inversion

One reason we should be suspicious of the yield curve inversion signal is that most economic indicators show a currently strong U.S. economy. The only storm clouds on the horizon are produced by the trade war with China. And, as I discussed in the post Trade War With China: U.S. Economy and Stock Markets, August 2019, we have several reasons for believing this trade war will not derail the economy. Domestic demand for the fruits of the economy is very strong and, if anything, is becoming stronger. Unemployment is historically low, the labor force participation rate is slightly increasing, real personal income is rising, and retail sales are accelerating.

Another explanation, other than panicked American investors piling into long-term treasuries, is even more probable. A more likely cause than panicked U.S. investors is panicked foreign investors. They have become increasingly alarmed by their own declining economies. And their own central banks, especially in Europe, have removed their domestic bonds as a safe haven. Apparently believing in the Phillip’s curve, many central banks have decreased effective interest rates to below zero. This means a foreign investor would receive less back from their domestic bonds than they initially invested. Foreign investors would have to pay for the safety of holding a domestic bond. Why would they take a loss like that when they could instead buy an American bond with a positive coupon rate?

The evidence that this foreign capital flight into U.S. bonds is actually happening can be found in the plot below.

Council on Foreign Relations / Brad W. Setser

Note that the largest component of capital inflows comes from the foreign purchase of “portfolio debt”, i.e. U.S. corporate and government bonds. Therefore, the explanation for U.S. bond yield inversion is foriegn investors bidding up the price of long-term bonds.

The claims the U.S. is about to enter a recession, because the yield curve inversion predicts it, should be taken with a couple thousand grains of salt. Such claims by progressives and their allied pundits are motivated more by politics than by reality.

Views: 2,387