Do We Need Tariffs To Attack Foreign Trade Problems?

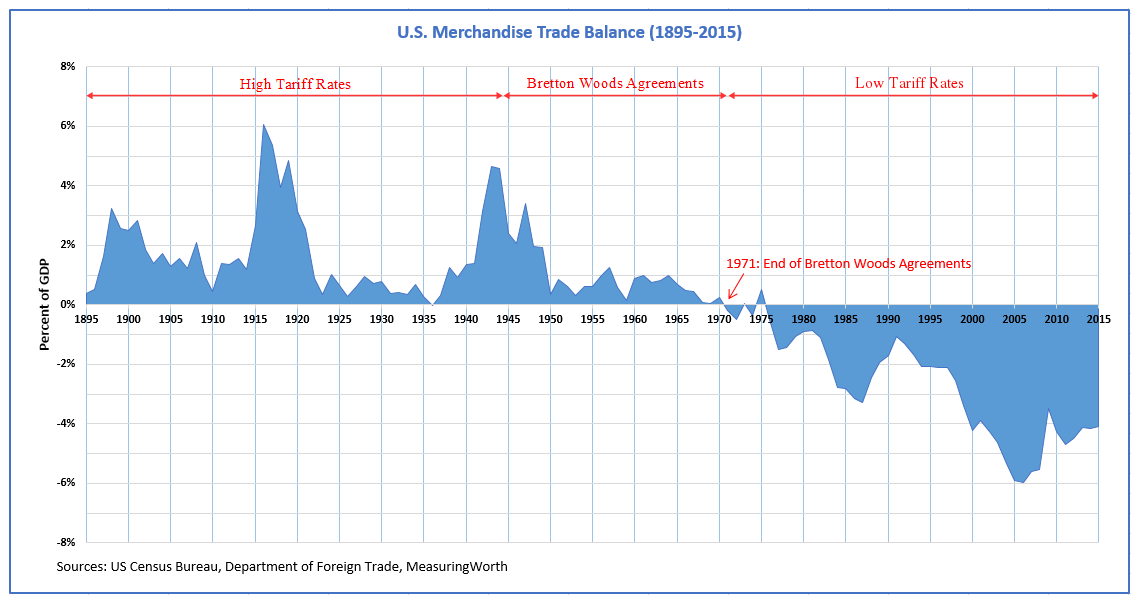

U.S. Trade Balance as a percent of GDP and Trade Policies from 1895 to 2015

Wikimedia Commons / James4

The plot above is highly suggestive of what has caused our trade difficulties. It is a plot over time of the difference in the dollar value of all American exports and imports as a percent of U.S. GDP. Earlier in our history, when import tariffs were generally high all over the world, we consistently exported more to other countries. During the years of the Great Depression in the 1930s, our positive balance of payments fell, probably because of the global decrease in economic activity. The trade balance again became large and positive during the World War II years, almost certainly because of U.S. exports of munitions to allies. Following World War II, however, tariffs were gradually negotiated downward. This was first done under the aegis of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and then under GATT’s successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO). As import tariffs came down globally, the positive U.S. trade balance also declined until finally it became permanently negative in 1976. That is the history in a nutshell. What should we want? Just as important, how can we get it?

The Foreign Trade Ideal and Why We Do Not Have It

The many opponents of free-trade will look at the trade balance plot above and declare the problem is obvious: Low import tariffs allow cheap foreign goods to out-sell our more costly goods. Countries that give lower wages to their workers can often produce lower cost goods of similar or better quality. However, this explanation ignores some very important parts of the problem. What it does not recognize is a large part of why the law of comparative advantage is supposed to work. Assuming of course, countries even allow the law to work.

For the law of comparative advantage operates only in environments where free-markets are allowed to function. It is more the expression of how the ideal conditions of free-markets would cause all countries to prosper with trade. Unfortunately, governments on both the importing and exporting sides can easily create policies that impair foreign trade’s ability to produce global prosperity.

One of the most elementary ways for understanding comparative advantage is to think about foreign trade as a way for countries to find a division of labor in producing wealth. Even if one country can produce all things at lower cost than another country, it should still concentrate on producing those goods for which it has the greatest advantage. Then it should buy the other goods for which another country has a comparative advantage from that country.

The law is usually expressed in terms of the relative costs in the two countries of producing pairs of different goods. Whatever the paired goods are (e.g. wine and clothing, airplanes and cars, etc.), I will abstractly give them the names α and β. Let the cost of production in country A for these two goods be given by CAα and CAβ, respectively, with similar notation for the costs of production in country B. Then, take the ratio of the cost of A producing a unit of good α relative to that to produce good β. If this ratio, the relative production cost of α compared to that of β, is less than the similar ratio for country B, country A is said to have a comparative advantage in producing α. As an inequality, this is expressed by the following.

CAα / CAβ < CBα / CBβ

Taking the inverse of this inequality yields

CAβ / CAα > CBβ / CBα

If country A has a comparative advantage in producing α, then country B must necessarily have a comparative advantage in producing β. If A has a comparative advantage for a good over B, then an exporter in A can sell it to B for a greater profit than he could in his own country. Also, an importer in B can buy it for a smaller price than he would have to pay to any producer in his own country. This has to do with the fact each country will produce more economic wealth if it produces goods for which it has a comparative economic advantage. Consider the elementary explanation of the video below.

Why this arrangement works in maximizing wealth production for the importing country is much more than just getting cheaper goods from the exporter. In addition, the importing country no longer has to devote capital to produce the goods for which the exporter has a comparative advantage. Instead, that capital is released and can be reinvested in producing other goods for which the importer does have a comparative advantage. This is precisely where the government of the importer can screw up the works.

In order for released capital to be reinvested, the owners of the capital (companies and other investors) must have the motivation to reinvest it. That is, they must have the expectation of earning additional profits by reinvesting. However, in most Western countries during recent decades, governments have been making life difficult for companies, making it harder for them to earn profits. This has been especially true in the United States during the Obama era. Without a motivation to reinvest freed-up capital, companies in the past have often used it to buy back their own stock or to pay higher dividends to their stock holders.

It is especially important to recognize the economic sins of the importing countries in causing violations of the law of comparative advantage; it is usually only the sins of the exporters that are ordinarily discussed. Yet the sins of the exporters are also very important, and come in two different varieties. First, there are the exporter actions that explicitly violate the law of comparative advantage. The second set of sins, particularly associated with the People’s Republic of China, is the theft of intellectual property (IP). We will discuss the violations of comparative advantage first.

Tariffs and Violations of the Law of Comparative Advantage

How does an exporter violate the law of comparative advantage? One way is to set a price for a good that is close to or below its production cost. A second way is to set import tariffs for a good significantly higher than the import tariffs of the trading partner for the same good.

Suppose one country (say, China) sets the price of a good for foreign trade at or below its cost of production. Clearly, the motivation for this action can not be economic, at least not in the short term. In the short term this does (or should do) little harm to the importing country (say, the United States). To the U.S. this looks exactly like China has a comparative advantage with that particular good. Not only does the U.S. get the good cheaper than if the U.S. produced it, but the capital the erstwhile U.S. suppliers used to produce it can be redeployed for more profitable production. That redeployed capital can include the human labor capital of workers who used to produce the imported goods. If the U.S. does not exploit the released capital to produce goods for which the U.S. does have a comparative advantage, that is the fault of the U.S., not of China.

Yet, if the appearance of a Chinese comparative advantage is deceptive and China is selling a good close to or below its production cost (aka “dumping” it), China is setting up the importing country for a future economic disaster. China has been implicated with dumping steel exports and solar panels, both in the United States and Europe; aluminum exports, textiles, apparel, footwear, advanced materials, specialty chemicals, medical products, and plywood products in the U.S. What happens if China is successful in displacing much of a vital American industrial sector, such as the production of steel? Even were China predisposed to provide the U.S. with charity, they are a relatively weak economy. See the comparison of American and Chinese per capita GDP below to convince yourself of this fact.

Data source: the World Bank

China can not afford to provide goods at or below the cost of production for very long. More than that, there is a great deal of evidence China is not providing us this current charity out of the goodness of their hearts. Instead, they are motivated by at least two self-serving reasons. One is to mitigate a disastrous over-investment in production capacity for goods like steel. The second is to set the stage to increase their economic dominance over other parts of the world. When we come close to a great dependence on them for some vital good, we can expect no mercy from them.

How should the U.S. counter such a violation of free-trade? Trump’s answer appears to be to threaten the trade in these goods with confiscatory import tariffs, with the hope of getting China to negotiate a less painful solution. Yet what happens if China stubbornly refuses to see reason? In order for Trump’s threats to be effective as a negotiating tool, he must be ready to make good on them. Trump is not a bluffer, as he has just shown with the Syrians. He can not afford to be seen as merely bluffing if he is to be taken seriously by his international opponents.

Yet, a dependence on an increase in tariffs to solve the problems has severe problems of its own. There is always the possibility China might totally, or partially in an unacceptable way, reject the American position. Then if we depend on the imposition of tariffs, an all encompassing trade war could erupt in which all trade between China and the U.S. is cut off. This would be a situation deleterious to the economies of both nations, as well as to that of the world. Is there a way in which the American-Chinese disagreements could be handled without total trade war?

One possible response is to accept all the temporary advantages of China’s extraordinarily cheap, dumped goods and increase the production of other goods for which the U.S. undeniably has a comparative advantage. American companies would have to be the ones to decide how to redeploy their capital. Nevertheless, the American government could help by ensuring if U.S. companies found such profitable redeployments, they could easily and quickly accomplish it without undue government interference. This is something the Obama regime was never capable of doing.

The Trump administration and the Republican Congress have already started this kind of assistance. Trump has been deconstructing the regulatory state that had put a stranglehold on business activity. Just as important has been the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed last December. Between the two government responses, the profit motive to invest has been returned to U.S. companies. Recent economic statistics show they are responding.

Another helpful government reaction would be to assist companies and investors in identifying countries and goods for which the U.S. has a comparative advantage. The CIA already provides a large amount of data, including economic, for other countries on the internet. Perhaps they could increase their research to identify such American comparative advantages.

This kind of response however is too passive to send a message to China that their mercantilist behavior is not acceptable. A more robust offensive riposte would be to deny Chinese the ability to invest in U.S. companies with their hoarded dollars, or to buy American property. If the Chinese deny American businesses permission to do business within China, we could do the same to Chinese businesses seeking to enter the U.S. Any legislation authorizing the executive branch to enforce these kinds of reactions should also allow the President to offer an olive branch for good behavior. Should China allow more U.S. companies to enter China or to buy Chinese domestic assets, the President should have the power to reciprocate.

A second way China as well as other countries violate the law of comparative advantage is to set their import tariffs on a particular good much higher than the U.S. tariffs on their imported goods. What this does is to make the costs of American goods appear larger to Chinese customers, altering the calculation for comparative advantage. Suppose we denote the Chinese tariff on good α to be TCα, and the effective American cost of producing the good for China to be

CAα = CAα + TCα

Similarly, denote the American tariff on good α by TAα , and the effective Chinese production cost of the good for the U.S. as

CCα= CCα + TAα

It will then appear to everyone that China has a comparative advantage in producing α rather than good β if

CCα / CCβ < CAα / CAβ or (CCα + TAα) / (CCβ + TAβ) < (CAα + TCα) / (CAβ + TCβ)

This poses a problem if in fact the actual production costs say the U.S. has the real comparative advantage, i.e. if

CCα / CCβ > CAα / CAβ

The United States can reverse the inequality to regain the comparative advantage on α by either sufficiently increasing its tariff TAα , or to a very limited extent by decreasing the tariff on good β. Increasing the American tariff on α would discourage China from exporting the good to the U.S., albeit with the already noted risk of provoking a trade war. To avoid this danger, the U.S. would be better off to decrease the tariff on β to the extent it is possible. This would encourage the Chinese to export the good for which they possess an actual comparative advantage. However the ability to do this is sharply limited by the fact the tariff can not be reduced below zero. It is also limited by the reality that Chinese motivations in setting tariffs are as much political as economic. Should the Chinese be rigidly intransigent, there might be no escaping a trade war. Our only consolation would be such a conflict would be much more devastating to China than to the U.S.

Intellectual Property Theft and How To Deal With It

No economy can survive large-scale theft. Yet every year the Chinese steal as much as $600 billion from the U.S. economy through the theft of intellectual property (IP). China is implicated as the world’s largest thief of intellectual property, accounting for 50% to 80% of global IP theft. This is a problem that can not be solved by high import tariffs on Chinese goods. Even if the U.S. and Chinese economies are completely isolated from each other by trade war, the Chinese will have access to U.S. trade secrets and intellectual property through cyber attacks. Below is a map, once classified secret but now declassified, obtained by NBC showing locations of Chinese cyber attacks on U.S. computers between 2010 and 2015.

Each red dot represents a single Chinese cyber attack on private and government computer systems that succeeded in stealing corporate and military secrets. These included data on electrical power, telecommunications, and internet backbone infrastructure. They also stole sensitive information on U.S. military and civilian air traffic control systems. Also, the Department of Homeland Security identified nine major cyber attacks between July 2014 and June 2015 seeking the personal data of millions of Americans. It would appear China is not only seeking corporate proprietary information for making Chinese companies more internationally competitive, but they are also actively seeking ways to disrupt or destroy sensitive systems in the case of war with the U.S.

Such a large scale of IP theft from an authoritarian nation, even if done by individual Chinese companies, could only exist through the connivance and cooperation of the Chinese government. Already, individual Chinese companies can be sued in U.S. courts for damages for IP theft. However, we desperately need a way to punish the PRC government itself. Perhaps, the federal government could bring class action suits against the PRC on behalf of IP theft victims. Since the People’s Republic of China is one of the largest holders of U.S. Treasury bonds, a federal court might require China to surrender those bonds for payment of damages.

It may well be a trade war with China is inexorably inevitable. Like any war, there would be casualties on both sides. Probably, there would be a lot more for China than the United States because of the greater U.S. economic strength. Nevertheless, that fact would not lessen our pain. As noted above, we possess several alternatives to increasing tariffs for resisting mercantilist countries like China. We should try all of them.

Views: 2,854