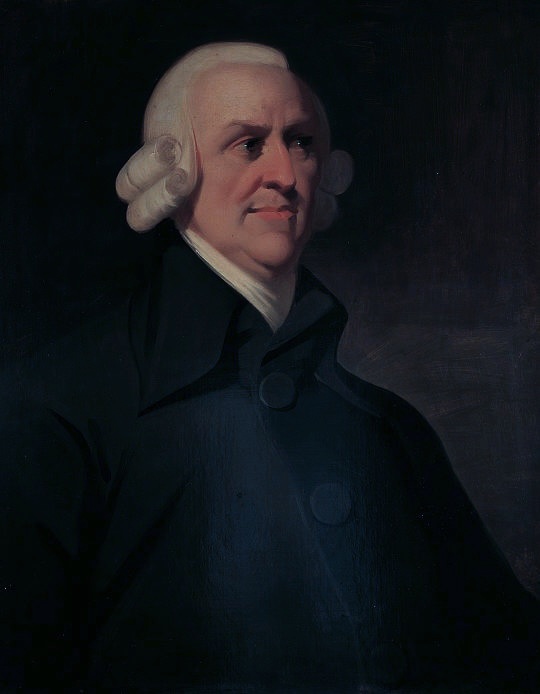

Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand

Although it might not be immediately obvious to you, the law of supply and demand implies one of the most important functions of money. Everyone knows money serves as a store of value and as a medium of exchange. But just as important is the role it plays in transmitting signals to producers as to what should (or should not) be produced and in what quantities. In other words, the signals transmitted to producers by the various prices of different goods informs the producers what the demand curves are. That is, it tells producers how much consumers are willing to buy at what price. Similarly, prices tell a consumer the relative costs of producing goods that he will have to reimburse in order to consume or possess any particular good. This includes the particular cost for reimbursing the entrepreneur for his time and labor in marshaling together all the factors required to produce and bring to market the good. This part of the total costs is usually called the producer’s profit. The price information tells the consumers what the supply curves are; i.e. how much a producer will sell at what price, Then, the individual consumer can decide how much of the good he would be willing to buy at any particular price.

One of the most famous quotes from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations is the following from Book I , Chapter II.

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

Also in Book IV, Chapter II he writes

But the annual revenue of every society is always precisely equal to the exchangeable value of the whole annual produce of its industry, or rather is precisely the same thing with that exchangeable value. As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can, both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce maybe of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain; and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

The emphasis in the second quote is mine. The language of 1776 is perhaps a bit turgid, but if you consider both of these quotes carefully you will discover this basic notion. A producer’s most basic motivation is to maximize his profits. But in doing so, he meets society’s needs and promotes its well-being. How does this happen? What is that invisible hand that leads him? What is the invisible hand that leads a consumer to decide which and how many goods to buy? That invisible hand is the price mechanism of a free market that leads both the producer and the consumer to find the equilibrium price point for each of the goods and services in society’s economy.

All of these considerations presuppose a perfectly free market. This is because only a market where no producer is coerced into selling a given number of goods at a given price, and no consumer is coerced into buying can find the good’s equilibrium price. The equilibrium price point is a balance between the needs of the producer and the needs of the consumer. If the needs of the producer are not met by receiving required sale revenues, he will not supply the number of goods needed by the consumer. If the needs of the consumer are not met, he will not buy all the goods produced, and a surplus with all of its costs is created. These needs are not necessarily knowable by a government that tries to fix the quantity and prices of goods. They are made knowable by the free interaction between producers and consumers.

The problem of finding the equilibrium price point is clearly a serious impediment for a state attempting central planning of the economy. It is often called the economic calculation problem. During the 1930s and 1940s, a Polish diplomat and socialist economist by the name of Oskar Lange developed an idea called market socialism to solve this problem. A socialist government would simulate a free market by first setting prices of goods by fiat, and then raising or lowering the price depending on whether a surplus or shortage was created. Unfortunately for the nations of the Soviet empire, this approach did not work. (See here and here and here and here.) Part of the reason for failure may be due to the slower reaction time of a bureaucratic committee setting prices compared to the near instantaneous speed that free market prices signal changes to producers and consumers alike. This is especially true today in a world interconnected with the world wide web. Yet another problem of market socialism is that prices of many different goods are interconnected in a complex pattern. Finding the optimum state of a many variable system is a very, very hard problem.

Views: 3,605